Evidence of Unconventional Oil and Gas Wastewater Found in Surface Waters near Underground Injection Site by USGS, May 9, 2016

These are the first published studies to demonstrate water-quality impacts to a surface stream due to activities at an unconventional oil and gas wastewater deep well injection disposal site.

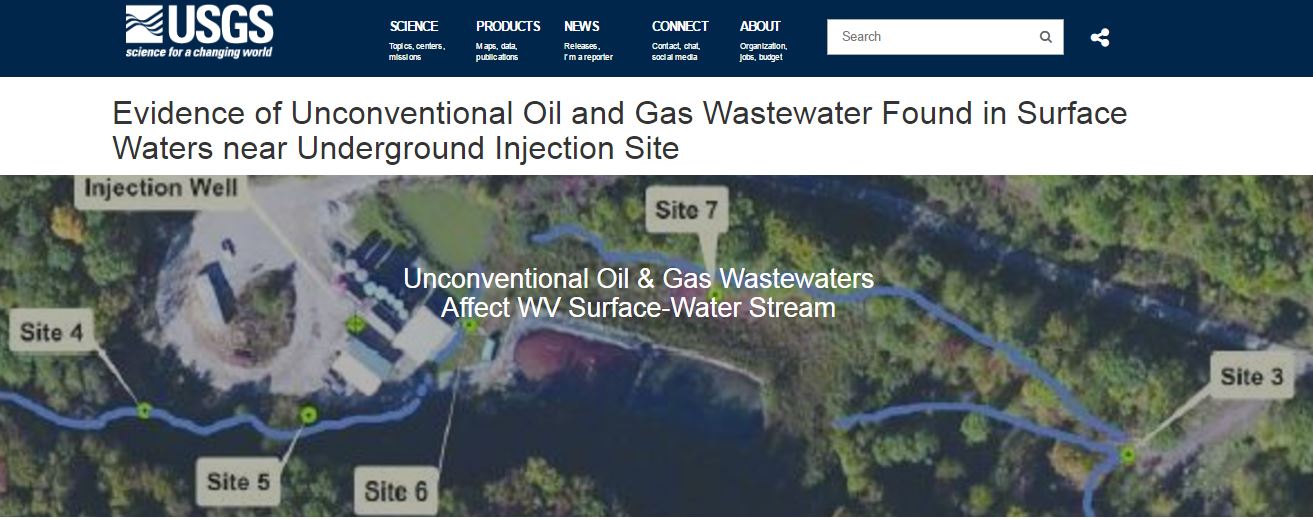

Evidence indicating the presence of wastewaters from unconventional oil and gas production was found in surface waters and sediments near an underground injection well near Fayetteville, West Virginia, according to two recent studies by the U.S. Geological Survey, University of Missouri, and Duke University.

These are the first published studies to demonstrate water-quality impacts to a surface stream due to activities at an unconventional oil and gas wastewater deep well injection disposal site. The studies did not assess how the wastewaters were able to migrate from the disposal site to the surface stream. The unconventional oil and gas wastewater that was injected in the site came from coalbed methane and shale gas wells.

“Deep well injection is widely used by industry for the disposal of wastewaters produced during unconventional oil and gas extraction,” said USGS scientist Denise Akob, lead author on the current study. “Our results demonstrate that activities at disposal facilities can potentially impact the quality of adjacent surface waters.”

The scientists collected water and sediment samples upstream and downstream from the disposal site. These samples were analyzed for a series of chemical markers that are known to be associated with unconventional oil and gas wastewater. In addition, in a just-published collaborative study tests known as bioassays were done to determine the potential for the impacted surface waters to cause endocrine disruption.

Waters and sediments collected downstream from the disposal facility were elevated in constituents that are known markers of UOG wastewater, including sodium, chloride, strontium, lithium and radium, providing indications of wastewater-associated impacts in the stream.

[More detailed summary provided by USGS:

What They Found

Scientists found evidence of UOG wastewaters in surface waters and sediments collected downstream from the disposal facility, specifically elevated concentrations of barium, bromide, calcium, chloride, sodium, lithium, strontium, which are known markers of UOG wastewater. Iron concentrations also increased and were in excess of West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection Agency water quality standard of one microgram per liter downstream of the UOG disposal facility. Microbial communities in downstream sediments had lower diversity and shifts in community composition compared to upstream locations, which could impact nutrient cycling due to altered microbial activity. Water samples adjacent to and downstream from the disposal facility exhibited evidence of endocrine disruption activity compared to upstream samples.]

“We found endocrine disrupting activity in surface water at levels that previous studies have shown are high enough to block some hormone receptors and potentially lead to adverse health effects in aquatic organisms,” said Susan C. Nagel, director of the EDC study and associate professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women’s Health at University of Missouri.

Scientists analyzed the microbial communities in sediments downstream. These microbes play an important role in ecosystems’ food webs.

“These initial findings will help us design further research at this and similar sites to determine whether changes in microbial communities and water quality may adversely impact biota and important ecological processes,” said Akob.

Production of unconventional oil and gas resources yields large volumes of wastewater, which are commonly disposed of using underground injection. In fact, more than 36,000 of these disposal wells are currently in operation across the United States, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the volume of unconventional oil and gas wastewater requiring disposal has continued to grow despite a slowing in drilling and production.

“Considering how many wastewater disposal wells are in operation across the country, it’s critical to know what impacts they may have on the surrounding environment,” [A few decades late?] said Duke University scientist Christopher Kassotis, the lead author on one of the studies. “These studies are an important first step in that process.”

Endocrine disruptors are chemicals that interfere with normal functioning of organisms’ hormones.

The studies were published in Environmental Science and Technology and Science of the Total Environment and can be found here. They are titled:

- “Wastewater disposal from unconventional oil and gas development degrades stream quality at a West Virginia injection facility,” with Akob as the lead author

- “Endocrine disrupting activities of surface water associated with a West Virginia oil and gas Industry wastewater disposal site,” with Kassotis as the lead author

This study is part of USGS research into the possible risks to water quality and environmental health posed by waste materials from unconventional oil and gas development. The USGS Toxic Substances Hydrology Program and the USGS Environmental Health Mission Area provide objective scientific information on environmental contamination to improve characterization and management of contaminated sites, to protect human and environmental health, and to reduce potential future contamination problems. [Emphasis added]

AND, ANOTHER NEW STUDY SHOWING FRACING CONTAMINATES SURFACE WATERS:

Duke Study: Rivers Contaminated With Radium and Lead From Thousands of Fracking Wastewater Spills by Sharon Kelly, Desmogblog.com, May 9, 2016, EcoWatch

[How many “spills” are the result of intentional dumping by companies and subcontractors?]

Thousands of oil and gas industry wastewater spills in North Dakota have caused “widespread” contamination from radioactive materials, heavy metals and corrosive salts, putting the health of people and wildlife at risk, researchers from Duke University concluded in a newly released peer-reviewed study.

Some rivers and streams in North Dakota now carry levels of radioactive and toxic materials higher than federal drinking water standards as a result of wastewater spills, the scientists found after testing near spills. Many cities and towns draw their drinking water from rivers and streams, though federal law generally requires drinking water to be treated before it reaches peoples’ homes [BUT NOT FOR FRAC CHEMICALS OR RADIOACTIVE TOXICS] and the scientists did not test tap water as part of their research.

High levels of lead—the same heavy metal that infamously contaminated water in Flint, Michigan—as well as the radioactive element radium, were discovered near spill sites. One substance, selenium, was found in the state’s waters at levels as high as 35 times the federal thresholds set to protect fish, mussels and other wildlife, including those that people eat.

[Compare to drinking water pollution in Alberta:

The pollution was found on land as well as in water. The soils in locations where wastewater spilled were laced with significant levels of radium and even higher levels of radium were discovered in the ground downstream from the spills’ origin points, showing that radioactive materials were soaking into the ground and building up as spills flowed over the ground, the researchers said.

The sheer number of spills in the past several years is striking. All told, the Duke University researchers mapped out a total of more than 3,900 accidental spills of oil and gas wastewater in North Dakota alone.

[And how many in only one year in New Mexico? A recent report says that nearly 1,500 oil, produced water and gas spills were reported in 2015.]

Contamination remained at the oldest spill site tested, where roughly 300 barrels of wastewater were released in a spill four years before the team of researchers arrived to take samples, demonstrating that any cleanup efforts at the site had been insufficient.

“Unlike spilled oil, which starts to break down in soil, these spilled brines consist of inorganic chemicals, metals and salts that are resistant to biodegradation,” said Nancy Lauer, a Duke University PhD student who was lead author of the study, which was published in Environmental Science & Technology. “They don’t go away; they stay.”

“This has created a legacy of radioactivity at spill sites,” she said.

The highest level of radium the scientists found in soil measured more than 4,600 Bequerels per kilogram [bq/kg]—which translates to roughly two and half times the levels of fracking-related radioactive contamination discovered in Pennsylvania in a 2013 report that drew national attention. To put those numbers in context, under North Dakota law, waste more than 185 bq/kg is considered too radioactive to dispose in regular landfills without a special permit or to haul on roads without a specific license from the state.

And that radioactive contamination—in some places more than 100 times the levels of radioactivity as found upstream from the spill—will be here to stay for millennia, the researchers concluded, unless unprecedented spill clean-up efforts are made. [What a way to make oil and gas companies happy!]

“The results of this study indicate that the water contamination from brine spills is remarkably persistent in the environment, resulting in elevated levels of salts and trace elements that can be preserved in spill sites for at least months to years,” the study concluded. “The relatively long half-life of [Radium 226] (∼1600 years) suggests that [Radium] contamination in spill sites will remain for thousands of years.”

Cleanup efforts remain underway at three of the four sites that the Duke University research team sampled, a North Dakota State Health Department official asked to comment on the research told the Bismarck Tribune, while the fourth site had not yet been addressed. He criticized the researchers for failing to include any in-depth testing of sites where the most extensive types of cleanup efforts had been completed.

The four sites the researchers sampled instead included the locations of two of the biggest spills in the state’s history, including a spill of 2.9 million gallons in January 2015 and two areas where smaller spills occurred in 2011. The samples from the sites were collected in June 2015, with funding from the National Science Foundation and the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group.

Over the past decade, roughly 9,700 wells have been drilled in North Dakota’s Bakken shale and Bottineu oilfield region—meaning that there has been over one spill reported to regulators for every three wells drilled.

“Until now, research in many regions of the nation has shown that contamination from fracking has been fairly sporadic and inconsistent,” Avner Vengosh, professor of geochemistry and water quality at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, said when the study was released. “In North Dakota, however, we find it is widespread and persistent, with clear evidence of direct water contamination from fracking.”

Dealing with wastewater generated by drilling and fracking has proved to be one of the shale industry’s most intractable problems. The industry often pumps its toxic waste underground in a process known as wastewater injection. Every day, roughly 2 billion gallons of oil and gas wastewater are injected into the ground nationwide, the Environmental Protection Agency estimates. Wastewater injection has been linked to swarms of earthquakes that have prompted a series of legal challenges.

The sheer volume of waste generated by the industry—particularly from the type of high volume horizontal hydraulic fracturing used to tap shale oil and gas—has often overwhelmed state regulators, especially because federal laws leave the waste exempt from hazardous waste handling laws, no matter how toxic or dangerous it might be, under an exception for the industry carved out in the 1980’s.

This leaves policing fracking waste up to state inspectors and not only do the rules vary widely from state to state, but enforcing those rules brings its own difficulties.

State inspectors have faced escalating workloads as budgets have often failed to keep pace with the industry’s rapid expansion. In North Dakota, the number of wells per inspector climbed from roughly 359 each in 2012 to 500 per inspector last year. In other states, the ratios are even more challenging, with Wyoming oil and gas well inspectors being responsible for more than 2,900 wells in 2015. And now, with the collapse of oil and gas prices, funds earmarked for oil and gas inspection have also nosedived in many states.

Lax enforcement may help explain why wastewater spills are so common across the U.S. More than 180 million gallons of wastewater was spilled between 2009 and 2014, according to an investigation by the Associated Press, which tallied the amount of wastewater spilled in the 21,651 accidents that were reported to state or federal regulators nationwide during that time.

The naturally occurring radioactive materials in that wastewater have drawn particular concern, partly because of their longevity in the environment and partly because the drilling industry enjoys looser federal standards for their radioactive waste than many other industries.

In January, North Dakota regulators further relaxed their standards for the dumping of radioactive materials, allowing many landfills in the state to accept drilling waste at levels higher than previously permitted, citing tough economic times for drillers.

… The spills the Duke University researchers identified often resulted from a failure to maintain infrastructure including pipelines and storage tanks. Roughly half of the wastewater spilled came from failed pipelines, followed by leaks from valves and other pipe connectors and then tank leaks or overflows.

But recent floods in Texas’s Eagle Ford shale region also highlight the risks that natural disasters in drilling regions might pose. Texas regulators photographed plumes of contamination around submerged drilling sites, a repeat of similar incidents in Colorado. “That’s a potential disaster,” Dr. Walter Tsou, former president of the American Public Health Association told the Dallas Morning News. [How fast will the “regulators” deregulate more to enable the disasters and toxic spills?]

Risks associated with fracking in flood zones have drawn the attention of some federal agencies in the past, but perhaps not in a way that locals in affected areas might find helpful.

In 2012, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program—a program designed to help people move away from areas subject to recurring floods—ran into a series of conflicts over oil and gas leases on properties that would otherwise be offered buy-outs. Some homeowners in Pennsylvania were denied the chance to participate in the program because of oil and gas leases or pipelines on their properties, as DeSmog previously reported.

In other words, it may be harder for those who have signed oil and gas or pipeline leases to abandon flood-prone areas, meaning that homeowners whose properties frequently flood could potentially face battles over cleanup costs without aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

And the newly published research from North Dakota suggests that the less visible brines may ultimately be more of a long-lasting environmental hazard than the spilled oil.

Even though their study included only leaks that were reported to state regulators, the researchers warned that little is currently being done to clean up sites where spills have occurred—or even to track smaller spills, especially on reservation lands, where roughly a quarter of the state’s oil is produced.

This means that the real amount of wastewater spilled is likely even higher than currently reported.

“Many smaller spills have also occurred on tribal lands,” Prof. Vengosh said, “and as far as we know, no one is monitoring them.” [Emphasis added]

[Where’s the frac pollution water monitoring in Canada?

Why no responsible response by Canadian water and energy regulators to all those recommendations year in, year out by Dr. John Cherry, enabled by the Munk School of Global Affairs Water Program? Were they just for show and spin (aka synergy) to enable the polluters to keep polluting and the regulators to keep lying and engaging in fraud?

Does Dr. Cherry know there will be no monitoring of the frac pollution? Is that why he allowed his Council of Canadian Academies Frac Panel to lie in their final report?

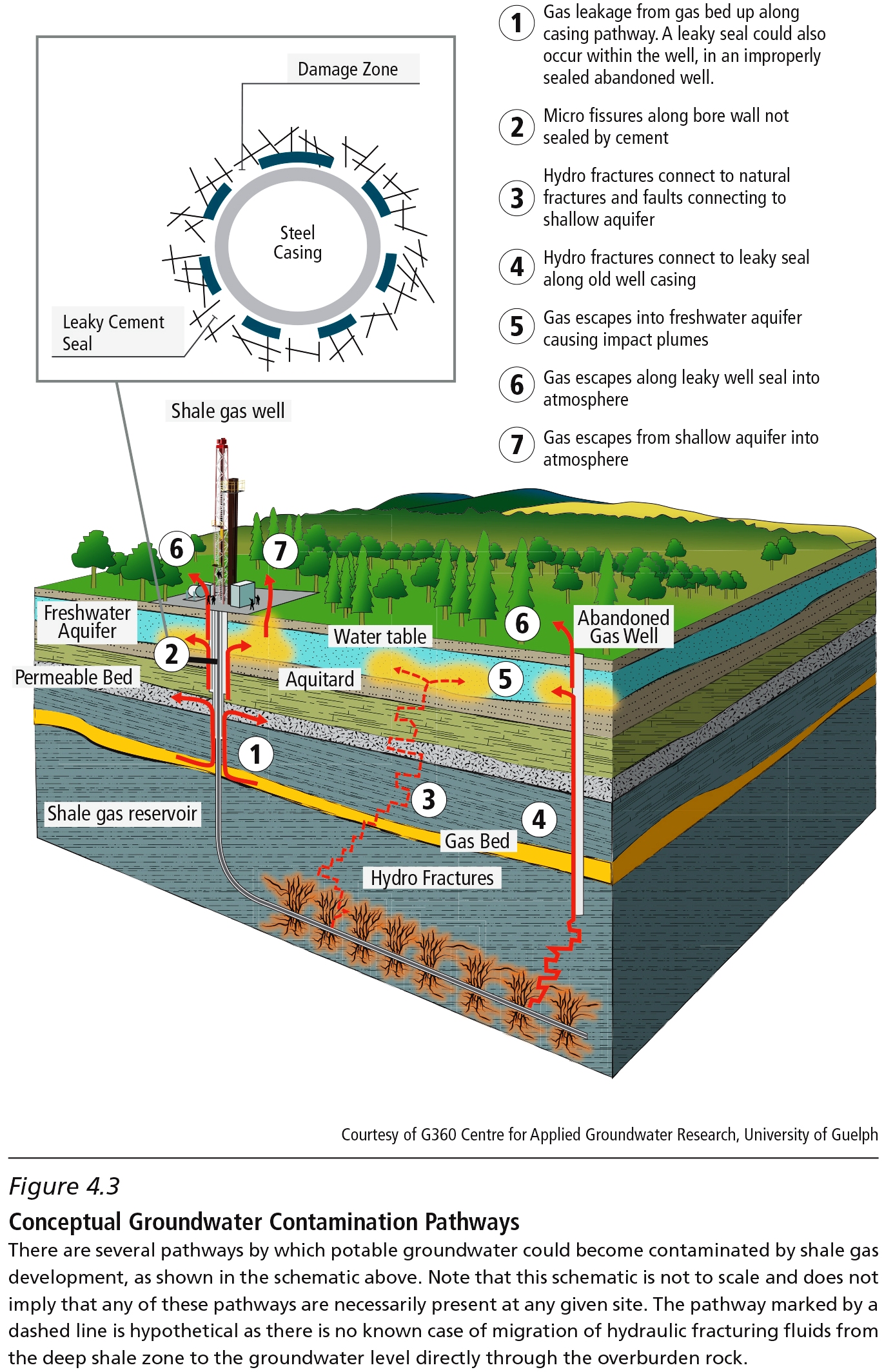

Below snaps from the report:

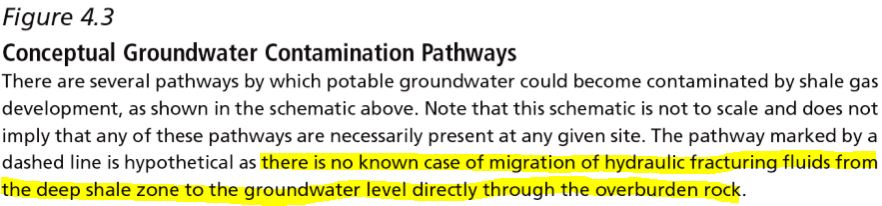

Text enlarged and highlighted below:

Snaps from Page 72 of the 2014 (fraudulent?) report by Dr. Cherry and expert panel of the Council of Canadian Academies frac report

***

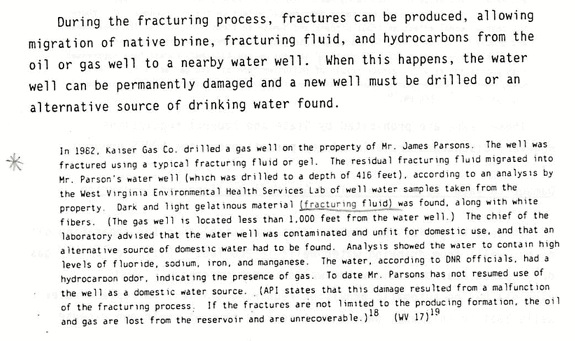

Compare to reality:

“….there is in fact a documented case, and the E.P.A. report that discussed it suggests there may be more. … The E.P.A.’s 1987 report does not discuss the specific pathway that the fracking fluid or gel took to get to Mr. Parsons’ water well in West Virginia or how those fluids moved from a depth of roughly 4,200 feet, where the natural gas well was fracked, to the water well, which was about 400 feet underground. …

This well was fracked using gas and water, and with far less pressure and water than is commonly used today. … “The evidence is pretty clear that the E.P.A. got it right about this being a clear case of drinking water contamination from fracking,” said Dusty Horwitt, a lawyer…who investigated the Parsons case. …

Mr. Parsons said in a brief interview that he could not comment on the case. Court records indicate that in 1987 he reached a settlement with the drilling company for an undisclosed amount.”

Article excerpts above with emphasis added, from: A Tainted Water Well, and Concern There May Be More by Ian Urbina, August 3, 2011, New York Times

Excerpt below from The New York Times 2011 Drilling Down Documents:

“This is a 1987 report to Congress by the Environmental Protection Agency that deals with waste from the exploration, development and production of oil, natural gas and geothermal energy. It states that hydraulic fracturing, also called fracking, can cause groundwater contamination. It cites as an example a case in which hydraulic fracturing fluids contaminated a water well in West Virginia. The report also describes the difficulties that sealed court settlements created for investigators.”

Cover of the 1987 EPA Report ]