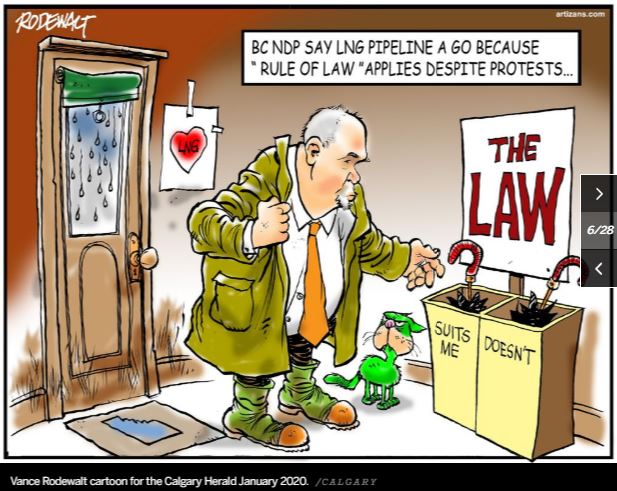

An excellent overview of Canadian “rule of law” by Robert Janes, lawyer, QC:

Robert Janes@rjmjanes Dec 29, 2020

Canada has to have a discussion about how injunctions, contempt of court and a Bleak House court system makes a mockery of the rule of law in the eyes of Indigenous people. …

Over the last ten years there has been judicial and police pushback on many of the gains made by Indigenous people in the courts through the use of injunctions and repeated entreaties to “respect the rule of law.”

In the criminal context (see Sun Peaks cases involving one of the Manuels) Section 35 defences could not be raised in response to mischief/nuisance charges because it would undermine the rule of law.

Likewise, in Behn case, the Supreme Court of Canada refused to allow a Section 35 treaty rights defence to be advanced in response to a law suit brought against an injunction because it would be an abuse of process and undermine the rule of law.

The irony there is that ultimately the actions of Mr. Behn were shown to be not unlawful although the court still denied him costs because, well, self-help is a bad thing.

The injunctions against the CGL project similarly have been used as a tool to cudgel Indigenous people while the prospect of any form of final judicial resolution of their claims is essentially laughable.

The injunction and rule of law case law ignores the reality of the accessibility of the courts for Indigenous people wanting to actually litigate their rights and use the courts to resolve matters in a peaceful way.

Summary proceedings are effectively not available for substantive infringement cases — see the court’s commentary in various cases (including West Moberly) on the need for pleadings, particulars, discovery and trial.

The standard of proof is overwhelming and counsel in these cases have no clear indication of where to stop — thus the need for experts, documents and an endless parade of witnesses grows with no limit in sight.

The effect of this is that trials are delayed by years to decades (Delgamuukw and Tsilhqot’in took decades to get to trial and then to the Supreme Court) and cost literally millions of dollars.

These costs are imposed on Nations — and in some cases individuals — who are amongst some of the most impoverished groups in Canada.

Even fighting procedural cases around the duty to consult – such as was the case with the TMX litigation – can cost into the millions of dollars and then all that happens is there is a do-over.

While there have been clear victories in the courts for Indigenous people (see the Tsilhqot’in case for example) the effective implementation of these cases has been delayed (see the Tsilhoqt’in case for example) with the courts giving limited effective relief.

All of this leads Indigenous people to look at the court system with a high degree of skepticism and contempt similar to that evoked by Dickens’ Bleak House about the Court of Chancery.

This contempt is particularly reinforced when there are examples out there of how direct action — even when sanctioned by the courts — gets results.

The CGL protests for example were severely criticized by the courts but resulted in Ministerial delegations being sent to deal with the Hereditary Chiefs and resulted in agreements in weeks that have not been reached in decades elsewhere.

Mr. Behn’s trapline has not been logged — despite his loss at the Supreme Court of Canada.

***

Emmett Macfarlane@EmmMacfarlane Prof of Political Science. Constitutional Law, Public Policy & Canadian Politics. Dec 29, 2020

The Supreme Court is a political institution.

David Minkley@david_minkley Replying to @EmmMacfarlane

The Canadian Supreme court?

Wash your hands and Wear a Mask@RebootRobertson Replying to @EmmMacfarlane

It’s a sad thought because it is true.

***

Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada announces a judicial appointment in the province of British Columbia Français Press Release by Department of Justice Canada, Dec 14, 2020, Canada News Wire

The Honourable David Lametti, Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, today announced the following appointments under the judicial application process established in 2016. This process emphasizes transparency, merit, and the diversity of the Canadian population, and will continue to ensure the appointment of jurists who meet the highest standards of excellence and integrity.

Ardith Walkem, Q.C., Lawyer at Cedar and Sage Law Corporation in Chilliwack, is appointed a Judge of the Supreme Court of British Columbia. Madam Justice Walkem replaces Madam Justice M. Gropper (Vancouver), who elected to become a supernumerary judge effective April 14, 2020.

Quote

“I wish Justice Walkem every success as she takes on her new role. I am confident she will serve the people of British Columbia well as a member of the Supreme Court of B.C.”

—The Hon. David Lametti, Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada

Biography

Justice Ardith (Walpetko We’dalks) Walkem, Q.C., grew up in Spences Bridge, B.C., and is a member of the Nlaka’pamux Nation. After completing a B.A. in Political Science and Women’s Studies at McGill, she attended law school at the University of British Columbia. She also earned a Master of Laws degree from UBC with a research focus on Indigenous laws.

Madam Justice Walkem articled at Mandell Pinder and McDonald and Associates. Practising with Cedar and Sage Law, she has worked extensively with Indigenous communities and organizations to support them in asserting their Aboriginal Title Rights and Treaty Rights. She is a mediator who also works within Indigenous dispute-resolution mechanisms. Her work has focused on the rights of children. She authored “Wrapping Our Ways Around Them: Indigenous Communities Child Welfare” (for the ShchEma-mee.tkt project) to support Indigenous communities in implementing their own child welfare laws or to work within existing child welfare regimes and to educate the legal community on how to work effectively with Indigenous peoples.

Access to justice has been a focus of Justice Walkem’s practice, and she has worked with organizations such as the Legal Services Society (Legal Aid B.C.), the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, and the B.C. Human Rights Tribunal (authoring “Expanding Our Vision: Cultural Equality & Indigenous Peoples’ Human Rights”). She co-chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Committee (TRC) advisory committee of the Law Society of B.C. and sat on the Continuing Legal Education Society of British Columbia’s TRC advisory committee, with the aim of encouraging reconciliation and understanding.

Justice Walkem lives in Chilliwack with her wife, Halie, and their two daughters, Sophia and Hannah.

Quick facts

- At the Superior Court level, more than 430 judges have been appointed since November 2015. These exceptional jurists represent the diversity that strengthens Canada. Of these judges, more than half are women, and appointments reflect an increased representation of visible minorities, Indigenous, LGBTQ2+, and those who self-identify as having a disability.

- The Government of Canada is committed to promoting access to justice for all Canadians.

“Promoting” it doesn’t mean all have it. Why not commit to guaranteeing access to justice for all? That would mean something. Law-violating corporations and their enabling, law-violating regulators have access to justice (and worse, judges ask them to pick their preferred judges when defendants in a lawsuit), as do judges, lawyers, the law-violating rich and criminals, rapists and pedophiles, but not ordinary non-criminal Canadians.

“Promoting” it doesn’t mean all have it. Why not commit to guaranteeing access to justice for all? That would mean something. Law-violating corporations and their enabling, law-violating regulators have access to justice (and worse, judges ask them to pick their preferred judges when defendants in a lawsuit), as do judges, lawyers, the law-violating rich and criminals, rapists and pedophiles, but not ordinary non-criminal Canadians. To improve outcomes for Canadian families, Budget 2018 provides funding of $77.2 million over four years to support the expansion of unified family courts, beginning in 2019-2020. This investment in the family justice system will create 39 new judicial positions in Alberta, Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

To improve outcomes for Canadian families, Budget 2018 provides funding of $77.2 million over four years to support the expansion of unified family courts, beginning in 2019-2020. This investment in the family justice system will create 39 new judicial positions in Alberta, Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador. - Federal judicial appointments are made by the Governor General, acting on the advice of the federal Cabinet and recommendations from the Minister of Justice.

- The Judicial Advisory Committees across Canada play a key role in evaluating judicial applications. There are 17 Judicial Advisory Committees, with each province and territory represented.

- Significant reforms to the role and structure of the Judicial Advisory Committees, aimed at enhancing the independence and transparency of the process, were announced on October 20, 2016.

SOURCE Department of Justice Canada

For further information: media may contact: Rachel Rappaport, Press Secretary, Office of the Minister of Justice, 613-992-6568, email hidden; JavaScript is required; Media Relations, Department of Justice Canada, 613-957-4207, email hidden; JavaScript is required

‘It’s about time’: Leading First Nations law expert named to B.C. Supreme Court, Newly appointed B.C. Supreme Court judge described as calm, but powerful. “Like the ocean.” by Dan Fumano, Dec 23, 2020, Vancouver Sun

![MANDATORY CREDIT: Nadya Kwandibens of Red Works Studio

UNDATED -- Ardith Walkem is the first Indigenous woman named a Justice on the BC Supreme Court. (MANDATORY CREDIT: Nadya Kwandibens of Red Works Studio) (For Dan Fumano story) [PNG Merlin Archive]](https://smartcdn.prod.postmedia.digital/vancouversun/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/259102037-ardith_walkem-w.jpg?quality=90&strip=all&w=288)

Even though Ardith Walkem was wearing a suit and pulled a big, rolling lawyer’s briefcase behind her on her very first day in court, people made the wrong assumptions about her.

Walkem, a member of the Nlaka’pamux First Nation, was a young lawyer in the late 1990s representing two hunters in a trial in Duncan, in Vancouver Island’s Cowichan Valley. Walkem arrived at the courthouse early that morning, where she was promptly approached by an RCMP officer.

The Mountie assumed Walkem was a victim of domestic violence, and asked if she needed assistance, she recalled in a 2017 video. Less than two minutes later, Walkem was approached by duty counsel, a Legal Aid lawyer who helps low-income defendants, asking whether she had representation for her criminal matter that day.

“Even though I was wearing a suit, even though I was carting that big lawyer briefcase, no one assumed that I was a lawyer,” Walkem said, describing the incident in the video produced for the Continuing Legal Education Society of B.C. and the Law Society of B.C. “Everyone assumed that I was there either as a victim of violence or to face criminal charges.”

Walkem built a celebrated legal career over the next three decades but continued to encounter racism in courthouses around B.C. More than once, Walkem recalled, lawyers asked her to leave the barrister’s lounges, telling her: ” ‘This is a space for lawyers only, you’re going to have to step out.’ ”

Soon, though, Walkem will trade in her lawyer’s suit for judge’s robes.

After the federal government’s announcement last week that Walkem had been appointed as a judge to the B.C. Supreme Court, Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs hailed what he called a “tremendous achievement, recognizing that her appointment makes her the first First Nations woman in this role in British Columbia.”

Walkem has practised in Indigenous law since she was called to the bar in 1996, and much of her work has focused on land and resource use, as well as the rights of children. She has acted at all levels of court, including the Supreme Court of Canada, co-chaired the Law Society of B.C.’s Truth and Reconciliation Committee advisory committee, and has owned and operated her own law firm for decades.

Walkem’s practice has also focused on access to justice, and she has worked with organizations including the Legal Services Society, the B.C. Human Rights Tribunal, and the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs.

It’s been a trying year for the Nlaka’pamux Nation in B.C.’s Interior, with the COVID-19 pandemic creating many challenges, said Nlaka’pamux tribal council executive director Debbie Abbott. So when Abbott received a text message last week from Walkem, who had been working with the tribal council on child welfare issues, asking her to call about something “urgent,” Abbott said she “wasn’t expecting it to be happy news.”

Instead, Abbott said, “we were so very, very proud to hear the good news, and brought to tears.”

Abbott said: “When I spoke to her, I said: ‘You will do good things.’ And she all of a sudden went very quiet. And I was like: ‘Well, that’s the truth.’ ”

Early in Walkem’s career she articled at Mandell Pinder, at a Vancouver firm specializing in Aboriginal law. Louise Mandell, one of the firm’s founding partners, said Walkem has “a fierce sense of justice, combined with a warm sense of humour.”

“She travelled a path that no other judge has followed to the bench,” Mandell said. “She came up in her own way, and she is … going to be a judge in her own way.”

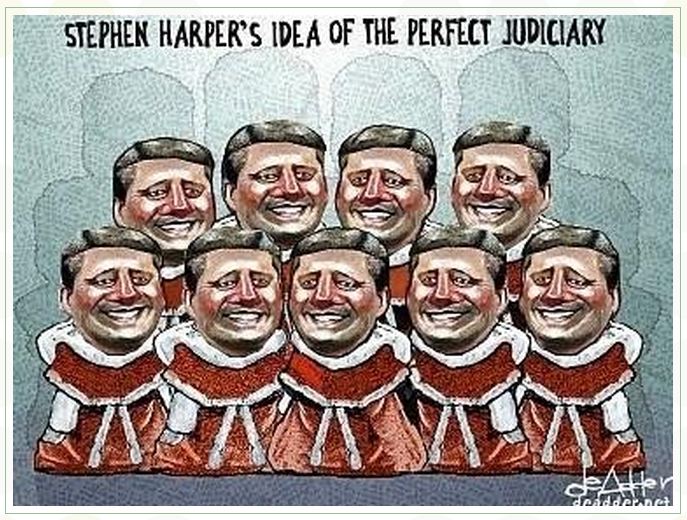

Walkem will likely work alongside some judges who have never had Indigenous colleagues or friends, Mandell said, “and they’re going to experience her brilliance, her kindness, and the warm sense of humour, they’re going to become friends with her in a way that changes the family portrait of the judiciary.”

![]() This portrait?

This portrait?

2013 Cartoon by Michael de Adder![]()

“It’s not just to bring that perspective to the bench, it’s actually to help indigenize the bench,” Mandell said.

“She’s experienced things that most of them never have, and just to know her, that relationship will make them better judges too.”

Walkem grew up in Spences Bridge and now lives in Chilliwack with her wife, Halie, and their daughters, Sophia and Hannah. Walkem declined to be interviewed. Those who know her described her as quiet and reserved, but assertive and authoritative.

Patricia Barkaskas, a Métis lawyer and associate professor of teaching at the University of B.C.’s Peter A. Allard School of Law, described Walkem as calm but powerful. “Like the ocean.”

“She doesn’t take up space in a loud way. She leaves that space for others, to bring them to the table and to add as many voices as possible,” Barkaskas said. “But when she walks into the room she just has such a powerful presence … She is a force to be reckoned with.”

“It shouldn’t be 2020 and this is the first First Nations woman appointed to the B.C. Supreme Court,” said Barkaskas. “But she certainly will not be the last, and that is something we can all look forward to … It’s about time.”

Refer also to:

2020: “For the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan peoples, justice has been denied. What else is new?”

Comment by Jan Steinman to the Tyee article in above post:

I’m not surprised at the BC Supreme Court ruling. It is chock-a-block full of Harper appointees.

[Seven out of nine of the Supreme Court of Canada justices who ruled in Ernst vs AER (seriously jeopardizing our Charter) and intentionally published smears/lies about Ernst, were also appointed by Harper.]

2019: How prevalent is racism (and misogyny) among Canadian lawyers & judges?

2018: Val Napoleon: Indigenous scholar, law professor at University of Victoria embraces disruption

Painting by Val Napoleon