One West Virginia County Tried to Break Its Dependence on the Energy Industry. It was Overruled. After seeing the scars of coal, Fayette County banned the disposal of natural gas drilling waste. Industry fought back, arguing the community doesn’t get a say by Ken Ward Jr., May 4, 2018, The Charleston Gazette-Mail

This article was produced in partnership with the Charleston Gazette-Mail, which is a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network.

FAYETTEVILLE, W.Va. — Matt Wender’s vision for Fayette County begins with the New River Gorge. Whitewater rafters, hikers and mountain bikers congregate there every summer. Craft beer and artisan pizza are helping his home emerge as an outdoor tourism hub.

Just upstream from the river, there’s another reality: A company called Danny Webb Construction Inc. pumps waste from natural gas drilling underground. Chloride, strontium, lithium and other markers of gas waste have been found in Wolf Creek, which flows into the river.

In the southeast corner of the county, developers of a 300-mile gas pipeline hope to turn a wooded, 130-acre plot into the site of a gas compressor station, a facility local leaders say would be noisy and would change the inviting nature of the area.

Fayette County is more than 150 miles from the vast reserves in Northern West Virginia that fueled skyrocketing gas production over the past decade. But the infrastructure to support the drilling crisscrosses the state: new pipelines, a host of processing plants, compressor stations and — industry supporters hope — a new generation of sprawling chemical factories and manufacturing plants.

Residents here know both the costs and benefits of serving the country’s energy needs. As recently as a decade ago, roughly 1,200 coal miners worked in Fayette County. Today, there are only about 600.

When Wender, one of three Fayette County commissioners, drives around the county where he grew up, he sees signs of its former life as a coal-mining community: scarred land and polluted creeks. There’s some progress, like the new national Boy Scout camp, built partly on abandoned mine sites reclaimed with federal funding. But there’s also the town of Minden, where federal officials are back again — after a series of failed cleanups — trying to figure out what to do about lingering pollution left behind by a long-closed equipment shop that served the coal industry.

Two years ago, Wender and his fellow commissioners decided they would fight for a different future. In early 2016, prodded by citizen concerns about pollution, they passed a local ordinance that prohibited disposal of natural gas drilling wastes in their county.

Amid a natural gas boom, communities across the country have pushed to put limits on drilling and waste disposal. But Wender, his fellow commissioners and the residents of Fayette County soon found out that taking on natural gas isn’t any easier than it’s been for decades for other West Virginia communities to take on coal. The state’s laws create an almost insurmountable bar.

The day after Fayette County leaders enacted their ban, EQT Corp., a Pittsburgh-based company that is West Virginia’s second-largest gas producer with $1.5 billion in income in 2017, filed suit. Company lawyers said the ordinance was so broad that it would halt any gas production in Fayette.

On the morning of an evidentiary hearing, in June 2016, Wender and a few dozen Fayette County residents drove more than an hour over winding roads to Charleston, so they could fill the courtroom. Wender planned to tell the county’s story. The county’s lawyers lined up a Duke University scientist to describe the pollution found downstream from Danny Webb’s site.

Just before the hearing, U.S. District Judge John T. Copenhaver Jr. issued a 45-page ruling that threw out Fayette’s waste disposal ban. No hearing was needed to gather facts, the judge said. It was strictly a legal issue, and the law, at least in this case, was clear: Federal and state statutes govern such matters; county officials can’t ban drilling in their own community.

The state of West Virginia “has concluded that oil and natural gas extraction is a highly valuable activity subject to centralized environmental regulation by” the state Department of Environmental Protection, the judge wrote. The County Commission “cannot interfere with, impede, or oppose the state’s goals.”

There was no testimony. Wender didn’t take the stand. The Duke scientist headed back to North Carolina.

As the judge left the bench, Fayette County residents stood, each with an arm held in the air and a fist clenched. They loudly hummed “America the Beautiful” as they filed out of the courtroom.

“I Didn’t Know It Was Bad Stuff”

For more than 20 years, Wender worked in his family’s department store in Oak Hill, about 10 minutes down the road from Fayetteville. He also was an investment manager at a state government economic development agency. When he was younger, he was not among those who tried to fight coal companies or strip mining.

“I didn’t really pay that much attention,” Wender said. “I was a retailer and I had miners who had pay in their pockets.”

Wender was first elected to the County Commission in 2000, and is running this year for his fourth six-year term.

By 2013, Wender was starting to hear more frequently from Fayette County residents about a natural gas waste disposal site in their community.

“I guess at the time I didn’t even know what fracking fluid was,” Wender recalled. “I didn’t know it was bad stuff.”

Just south of Fayetteville, the county seat, toward the end of a narrow road off the four-lane highway, Danny Webb had, for more than 10 years, been pumping natural gas industry wastes into one, and then two “injection wells.”

Modern natural gas drilling uses huge quantities of water, and generates equally large quantities of waste fluids. The Danny Webb wells have disposed of wastewater for dozens of major producers, an important service to the state’s natural gas industry.

Danny E. Webb, president of his namesake company, has said the waste injection is safe and generally complies with state permit requirements.

The Danny Webb wells are located near the community of Lochgelly, along Wolf Creek, which flows into the New. A few miles downstream, West Virginia American Water Co. draws water for its regional plant, which provides drinking water for 25,000 people.

Local residents had been around and around with Danny Webb about odors, water pollution and health concerns. Complaints to the DEP. Permit hearings. Appeals.

In one instance, West Virginia regulators allowed Danny Webb to keep pumping waste into the ground even after his permit had expired. In another, the DEP renewed Danny Webb’s permit, even though the landowner for the site had terminated the lease that granted Danny Webb the authority to operate there.

Citizens walked away feeling like the laws they thought were supposed to help them were actually written — or were being enforced — to protect the industry.

The scene in June 2013, during a public hearing at Oak Hill High School, was pretty typical.

The DEP had set up the meeting to hear what local residents had to say about the company’s request to renew its permit. Residents felt the agency had not been tough enough after previous problems at the site. They worried that the DEP wasn’t going to protect their water.

“I’m a computer programmer, and I can live anywhere and work from anywhere, and I chose to move to Fayetteville,” resident Jessica Rice said. “But had I known the kind of laissez-faire attitude of legislation and regulation, I’m not sure I would have.”

Jerry Cook, a resident of Lochgelly, described “a really foul odor” that comes from the injection-well site.

“There are days and nights, I can’t go on my porch,” Cook said. “I have to go in the house.”

This was all familiar territory for anyone who watched how West Virginia officials had dealt with the coal industry for decades.

Paul Brown, a former coal miner and a retired coal mine safety inspector, recalled how the state allowed coal companies to pump their wastes underground.

“I’m proud to be a coal miner, but I am not proud of what the DEP is doing to our drinking water,” Brown said. …

Speaking at the 2015 hearing, Trish Kicklighter, who was then the park superintendent, urged state regulators not only to shut down Danny Webb’s injection wells, but to block the entire watershed from any similar facilities in the future.

“The three national parks in this immediate area are the foundation stones of the local tourism industries,” Kicklighter said. “Water quality is directly linked to the success of the tourism industry in this area.”

Webb, the company president, defended his operations during a public hearing a month later. Over a dozen years, he said, state inspectors had cited only two violations, one for a faulty liner in a waste storage pond and another for a crack in a leak-containment dike. Webb noted that, in 2015, his company provided 14 jobs and would spend more than $1 million a year in Fayette County on equipment and truck fuel.

DEP officials also defended their handling of issues surrounding the Danny Webb facility. In a report responding to public comments at the time, the DEP said the operation was not a “chronic offender” and wasn’t “skirting the regulations.” A DEP spokesman did not respond to questions from the Charleston Gazette-Mail about the issue.

In 2016, two peer-reviewed studies, both co-authored by scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey, provided some support for concerns about the Danny Webb injection wells. One study reported that water and sediment collected downstream from the site showed signs of pollutants that could have come from the natural gas waste. The other study found high levels of chemicals that disrupt the body’s hormone system in water samples collected downstream from the site.

By then, Wender and his fellow county commissioners had decided to step in. Arguing that county officials have the right to protect their communities from activities that are a legal “nuisance,” commissioners declared that disposal of waste from natural gas production was an “intolerable public health and safety hazard.”

The county’s move brought quick legal action from natural gas producer EQT, which had more than 200 gas wells and operated one waste-injection well in the county.

EQT argued that the county ordinance violated state and federal laws — the West Virginia Oil and Gas Act and the federal Safe Drinking Water Act — that preempt any local regulation of the industry. Danny Webb sued a couple of days after EQT, citing similar arguments.

Tim Miller, a lawyer for EQT, argued that Fayette’s ban was written so broadly that it would prohibit the company from even storing liquid waste in tanks at its gas-producing wells in Fayette County. County commissioners tried to revise the ordinance to address those concerns, so the rule would focus on waste wells only.

While the powers of local communities vary somewhat from state to state, gas industry trade groups noted in a “friend of the court” filing that local efforts around the country to regulate natural gas drilling have almost uniformly been thrown out by the courts. Lawyers for Fayette County could point to only one case — in New York — where local rules survived legal scrutiny.

In some states, such as Texas, where local rules appeared likely to survive court scrutiny, the industry has pushed lawmakers to step in. These so-called “pre-emption” laws have been promoted by the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC. The group says statewide regulations are better for business than a “patchwork” of local rules.

A year after losing in district court, Fayette lost again, in August 2017, when the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals sided with EQT. That left county leaders stuck between a state regulatory system they didn’t trust and a federal court system that told local communities they didn’t have a say.

Since the court case concluded, two more studies have been published on the Danny Webb injection wells. The authors found contaminants only in parts of the creek close to the site, and not farther downstream — but called for more research into their impacts.

It’s not clear what is going to happen with the injection wells. Last year, the West Virginia Supreme Court upheld a move by a land company, the North Hills Group, to terminate its lease with Danny Webb for the property where the largest of the two waste-injection wells is located.

John Leaberry, a lawyer for Danny Webb, said that court decision cost the company an estimated 60 percent to 70 percent of its disposal capacity, which may threaten its economic viability. It also means natural gas producers in the area have to pay more to haul their waste to far-off disposal sites, he said.

“We had outside people who came in and made determinations that there were environmental problems associated with injection wells,” Leaberry said. “The state of West Virginia never made those same determinations.”

Taking a Stand

On a warm afternoon in late February, Wender munched on a cheeseburger at Cafe One Ten, in Oak Hill, and talked about the county’s latest battle with the natural gas industry.

EQT and a collection of other companies want to build the Mountain Valley Pipeline to carry natural gas from the Marcellus Shale region to markets in the South and on the East Coast. Opposition has been growing, spurred by the companies’ legal efforts to force unwilling landowners to turn over rights-of-way to build the pipeline on their properties.

The pipeline would run through only about 2,700 feet of Fayette County, just glancing a southeastern corner. But developers also want to build a large compressor station in that corner of the county, a rural area of forests and farms.

The compressor station could be loud and dirty, Wender said. “How would you feel if you had to live with the hum of that compressor station all the time?” he asked.

Unlike most of West Virginia’s 55 counties, Fayette has long boasted of a countywide zoning ordinance. And, it turns out, the area targeted for the compressor station isn’t zoned for industrial operations.

Last November, Wender and his fellow county commissioners rejected a request for a zoning change from the companies.

That same day, the pipeline developer’s lawyers sued the county in federal court.

In court filings, Miller — the same lawyer who represented EQT in the waste disposal case — said the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s approval of the pipeline, and not Fayette County’s zoning, is what decides the matter. Miller described the compressor station as “carefully designed” to “limit surface disturbance, and minimize the overall environmental footprint.” [Pfffft! Encana made the same bogus promises to Rosebud Alberta citizens. What the community got was not what the company arrogantly promised; Rosebud got hung with law-violating, health harming, ugly piece-of-shit noise makers]

Wender isn’t optimistic that things will go the county’s way this time, either. His lawyers tell him the National Gas Act, a federal law, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, give local communities very little say over pipelines or compressor stations.

Still, Wender isn’t ready to give up just yet. He says the county’s lawyers have been looking again at their previous natural gas waste disposal ordinance. They think they might have found a way to rewrite it that can withstand scrutiny by the courts.

“The fact is that we have this zoning and we try to be a model county, and along comes this Natural Gas Act and trumps all of that,” Wender said. “But there is some benefit to taking a stand.”

Refer also to:

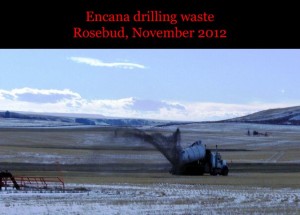

Encana dumping its waste on crop land at Rosebud, Alberta

annie_fiftyseven comment to Andrew Nikiforuk’s article in The Tyee

“There are more than 100 deep injection wells in northern B.C. The LNG industry could require the construction of hundreds more to support increased fracking.

In recent years the OGC has shut down three injection wells because of earthquake hazards and closed down another seven as their reservoir pressure reached its threshold.”

Disposing of industry’s toxic, radioactive waste is a huge problem “that’s just going to get bigger and bigger.”

August 29, 2018 – “‘Disposal nightmare’: In Permian Basin, every barrel of oil means four barrels of toxic water

… Overall, the region will pull up enough water this year alone to cover all of Rhode Island nearly a foot deep.

… Spending on water management in the Permian Basin is likely to nearly double to more than $22 billion in just five years, according to industry consultant IHS Markit. The reason is twofold. The rig count is rising, and many of the ‘workhorse’ disposal formations used for decades are starting to fill up, said Laura Capper, an industry consultant. That means explorers have to move water further to find a home for it.

It’s a problem ‘that’s just going to get bigger and bigger,’ said Wood Mackenzie analyst Ryan Duman, ‘Operators are victims of their own success.’

Drillers generally flush excess water back into the ground, often after trucking it to areas such as the San Andres, a region of the basin largely drilled-out early on in the shale boom. But now, with the boom hitting historic levels, that system is running into headwinds.

In the San Andres, wells sunk to gather oil deeper within the play are collapsing as a result of the increased pressure from water injections, causing dozens to be closed and the loss of miles of pipe, according to Andrew Hunter, a drilling engineer at Blackstone Energy Partners-backed Guidon Energy.

It’s a situation that’s ‘getting worse,’ Hunter said at a recent conference on water held in Houston. ‘I think people are afraid to talk about this problem. We’re trying to get the word out to let everyone know how serious this is.’

At the same time, earthquakes in parts of West Texas and New Mexico that include the Permian have more than tripled to 62 with at least a 2.5 magnitude in the past year, from just six two years earlier, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.”

Fortunately, there are plenty of solutions.

We can dump it on our roads:

July 2, 2018 – “Radium found in commercial roadway de-icing, dust suppression brine

An Ohio environmental organization is suing to learn more about unhealthy radiation levels in a commercial de-icing and dust suppression liquid made from gas well brine sold in several states, including Pennsylvania.

The Buckeye Environmental Network filed suit against the Ohio Department of Natural Resources last week, claiming the agency has illegally denied its request to inspect public records and documents pertaining to the environmental and health impacts of the brine product AquaSalina, manufactured by Brecksville, Ohio-based Nature’s Own Source.

According to a July 2017 ODNR report that was released early this year after the network filed a right-to-know request, the department found samples of AquaSalina that contained concentrations of radium, a known carcinogen, that are higher than those naturally occurring in brine produced from ‘conventional,’ that is non-shale, gas wells.

The ODNR’s Division of Oil and Gas Resources Management, Radiation Safety Section, tested 14 samples of AquaSalina collected from six locations in Ohio, and found radium 226 and 228 levels that exceeded the state’s ‘discharge to the environment limits’ and its safe drinking water limits by a factor of 300.

The study said the production process used by Nature’s Own Source seems to have produced ‘TENORM,’ or Technologically Enhanced Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material, that contains more radiation than the brine had when it was pushed out of the wells.

Among the sites where the ODNR obtained AquaSalina for testing in June 2017 was a Lowe’s home improvement store in Canton, Ohio, and a hardware store in Hartville, Stark County, south of Akron.

The Buckeye Environmental Network wants to inspect state records to determine where the product has been sold and used, and if follow up testing has been done as recommended by the initial study, said Teresa Mills, BEN’s executive director.

‘What is the agency trying to hide from the public?’ Ms. Mills said. ‘We requested to review all records held by the agency in order to determine how and if the agency plans to take steps to remove this product from the consumer market … [W]e believe that the public has a right to know how much radiation they have been or may be exposed to if they use this product.’

David Mansbery, Nature’s Own Source president, said he didn’t know about and hadn’t seen the ODNR report, but stressed that AquaSalina is ‘pure, natural, 400 million-year-old seawater.’

Mr. Mansbery said the product is filtered to remove volatile organic compounds and trace minerals, but ‘we don’t do anything to enhance or reduce any of the naturally occurring NORMS in the product.’

… Mr. Stolz said the ODNR report seems to show the brine production process used by Nature’s Own ‘is significantly enriching’ for both radium 226 and 228 — 11 to 92 percent — depending on the test location.

‘The levels in the de-icer were typically over 300 times the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency limit for drinking water and exceeded Ohio regulations,’ Mr. Stolz said. ‘I was concerned to see that the product purchased at the hardware store had total radium (226 and 228 combined) levels of 2,500 picocuries per liter, 500 times the U.S. EPA limit. It’s yet another reason for not using brine for road treatment, de-icing, and dust control.’”

We can eat it:

June 24, 2018 – Radioactive water reignites concerns over fracking for gas

“High levels of a radioactive material and other contaminants have been found in water from a West Australian fracking site but operators say it could be diluted and fed to beef cattle.”

We can eat more of it, and drink it too:

December 8, 2018 – “A push to make fracking waste water usable in agriculture — and even for drinking

… Aubrey Dunn, New Mexico’s outgoing land commissioner, said the state isn’t doing enough to incentivize treatment instead of injection. He supports state tax breaks for companies that treat the waste water so it can be used for agriculture or drinking.

… A 2015 study lead by a Duke University professor found that even treated waste water from the oil and gas industry had up to 50 times the amount of ammonium allowed by the EPA.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/a-push-to-make-fracking-waste-water-usable-in-agriculture–and-even-for-drinking/2018/12/07/9a22e496-f803-11e8-8d64-4e79db33382f_story.html?utm_term=.31aafc20e650

We can deliver it to unsuspecting citizens, to replace their industry-contaminated water supply:

December 4, 2014 – “The Nightmare of Ann Craft: Fracked, then Poisoned – Albertan says drilling buckled her property. Then the real misery started.

… For two years now Craft has been involved in a fight with the Alberta government over the structural damage to her property along with the appearance of strange substances on her land and dug-out along with changes to her well water due to oil and gas activity.

In addition, a private water hauler delivered a batch of toxic water to her cistern instead of potable water. Craft then bathed in it.”

https://thetyee.ca/News/2014/12/04/Nightmare-of-Ann-Craft/

And we can dump it in our rivers and streams:

October 18, 2018 – “EPA weighs allowing oil companies to pump wastewater into rivers, streams

For almost as long as there have been oil wells in Texas, drillers have pumped the vast quantities of brackish wastewater that surfaces with the oil into underground wells thousands of feet beneath the Earth’s surface.

But with concern growing that the underlying geology in the Permian Basin and other shale plays are reaching capacity for disposal wells, the Trump administration is examining whether to adjust decades-old federal clean water regulations to allow drillers to discharge wastewater directly into rivers and streams from which communities draw their water supplies.”

So, lots of solutions. Clearly, the world is industry’s oyster … and “mussel.”

October 22, 2018 – “Fracking wastewater accumulation found in freshwater mussels’ shells

Elevated concentrations of strontium, an element associated with oil and gas wastewaters, have accumulated in the shells of freshwater mussels downstream from fracking wastewater disposal sites, according to researchers from Penn State and Union College.

‘Freshwater mussels filter water and when they grow a hard shell, the shell material records some of the water quality with time,’ said Nathaniel Warner, assistant professor of environmental engineering at Penn State. ‘Like tree rings, you can count back the seasons and the years in their shell and get a good idea of the quality and chemical composition of the water during specific periods of time.’

In 2011, it was discovered that despite treatment, water and sediment downstream from fracking wastewater disposal sites still contained fracking chemicals and had become radioactive. In turn, drinking water was contaminated and aquatic life, such as the freshwater mussel, was dying. In response, Pennsylvania requested that wastewater treatment plants not treat and release water from unconventional oil and gas drilling, such as the Marcellus shale. As a result, the industry turned to recycling most of its wastewater. However, researchers are still uncovering the long-lasting effects, especially during the three-year boom between 2008 and 2011, when more than 2.9 billion liters of wastewater were released into Pennsylvania’s waterways.

Freshwater pollution is a major concern for both ecological and human health,’ said David Gillikin, professor of geology at Union College and co-author on the study. ‘Developing ways to retroactively document this pollution is important to shed light on what’s happening in our streams.’

… What the team found was significantly elevated concentrations of strontium in the shells of the freshwater mussels collected downstream of the facility, whereas the shells collected upstream and from the Juniata and Delaware Rivers showed little variability and no trends over time.

Surprisingly, the amount of strontium found in the layers of shell created after 2011 did not show an immediate reduction in contaminants. Instead, the change appeared more gradually. This suggests that the sediment where freshwater mussels live may still contain higher concentrations of heavy metals and other chemicals used in unconventional drilling. ‘We know that Marcellus development has impacted sediments downstream for tens of kilometres,’ said Warner. ‘And it appears it still could be impacted for a long period of time. The short timeframe that we permitted the discharge of these wastes might leave a long legacy.’

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, up to 95 percent of new wells drilled today are hydraulically fractured, accounting for two-thirds of total U.S. marketed natural gas production and about half of U.S. crude oil production.

‘The wells are getting bigger, and they’re using more water, and they’re producing more wastewater, and that water has got to go somewhere,’ said Warner. ‘Making the proper choices about how to manage that water is going to be pretty vital.'”

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/10/181022135716.htm