The very worst impulses of humankind can survive generations, centuries, even millenia.

And the best of our individual efforts can die with us at the end of a single lifetime.

Elizabeth Kostova, The Historian

The truth is that when an individual is fighting against big corporation, the regulator as well as the Supreme Court, became “willfully blind”. Very sad. And it is politic. In fact, the judiciary branch is far to be independent.

Natalia to Lorne Sossin’s “Damaging the Charter: Ernst v. Alberta Energy Regulator”

Jan 20 Justice Sossin by Peter Adourian, Feb 19, 2019, Charter Damages Blog

Lorne Sossin has metamorphosed into Justice Sossin.  And in Dec 2020 was appointed to the Court of Appeal for Ontario.

And in Dec 2020 was appointed to the Court of Appeal for Ontario. What does this mean for Charter damages?

What does this mean for Charter damages?

Dean, I mean, Justice Sossin was recently appointed to the Superior Court in Toronto. Among his scores of publications, Justice Sossin penned three important pieces on the how, when, and why of Charter damages. With several tributes to Justice Sossin floating around the internet, I thought it apt to highlight his contributions to this particular niche in the law.

1993: A Bold Idea: A Charter Compliant Government

In “Crown Prosecutors and Constitutional Torts: The Promise and Politics of Charter Damages”, Sossin laid out an argument for awarding Charter damages based on deterring unconstitutional government conduct.

The bold idea here is in how Sossin distinguished Charter damages from traditional tort-based damages. Unlike tort law, which focuses on the deservedness of the plaintiff to damages (and no more than deserved), Charter damages should focus on the rights of the claimant guaranteed by the constitution. Similarly, for the defendant, tort law focuses on the fault of the defendant; but to Sossin, Charter damages ought to focus on the compliance of government with the Charter.

In his words: “Crudely, it aims to oblige public officials to protect, or at least respect, the rights of private persons.”

His article is focused on the liability of Crown prosecutors, likely due to the renewed interest in this area after the Supreme Court’s decision in Nelles v Ontario. The Court had opened the door (albeit very slightly) for claims of malicious prosecution. Malice being the high threshold that it is, few claims are likely to succeed.

With his trademark wit, Sossin described Crown immunity based on malice in these terms: “either it immunizes prosecutors from the consequences of legal acts, which would be redundant, or it immunizes them from the consequences of illegal acts, which would be repugnant.”

Another shortcoming of the malice standard is that it seems to suggest that the rights of an accused are breached by rogue or dishonourable Crown lawyers. Sossin disagrees, arguing that many Charter breaches in the criminal justice system can be “traced to systemic practices or abuses” and therefore Charter damages must be aimed at bringing the system into Charter compliance.

He again quips, “the point of constitutional liability for prosecutors, in my view, is not to bring the rotten apples in line, but to keep watch on the barrel.”

He points to the Donald Marshall inquiry, suggesting that the “enduring misconception about the Marshall case is that it represented an isolated incident, rather than a rare public glimpse at a more widespread structural problem”. For these reasons, Charter damages should be used to disincentivize Crown attorney’s offices from pursuing or permitting unconstitutional practices within their departments.

Sossin departed from many of his contemporaries by entirely jettisoning compensation as a purpose for Charter damages. He argued that a system based on compensation would tend to favour the privileged accused over the indigent accused. This, he noted, is a problematic application of formal equality.

Instead, damages liability should target bad government action regardless of the accused’s personal loss in the circumstances.

This article, in my view, was as bold and controversial then as it is now. It departs significantly from the well-advanced American case law on the subject and even the more permissive Canadian literature promoting compensatory purposes rooted in tort law principles. This particular article remains relevant even after the Court’s leading decision in Vancouver (City) v Ward – released 17 years later – which permits compensatory damages (in addition to damages for deterrence) and left the door open for tort standards like malice to influence Charter damages.

It turns out that open door was pushed open in two subsequent Charter damages cases, and Sossin had something to say about it.

2016: A Bad Omen: Infusing Private Law Principles

Among his many responsibilities as Dean at Osgoode, Sossin opened the annual Constitutional Cases Conference with a review of the Supreme Court’s recent decisions. In 2016, the Court’s decision in Henry v British Columbia drew his ire, largely along the same points he raised in his 1993 article.

In Henry, a 4-2 majority of the Court placed some significant barriers to recovery of Charter damages against Crown prosecutors for constitutional breaches during the trial process. Sossin was less than impressed.

In particular, Sossin took issue with the majority’s reliance on private law principles to award a public law remedy. He repeated his concern that a focus on compensatory damages would privilege the rich over the poor. He refers to an unlawful search and seizure in a rich person’s home that damages a priceless heirloom and a similarly unlawful search in a homeless person’s makeshift dwelling. Compensatory principles, applied in Charter cases, would have an awful result: “quite literally some people’s rights will be more valuable than others.”

He takes issue with the Court’s justification for a high threshold of fault. The Henry case was about a wrongful conviction caused largely by the prosecution’s failure to meet its constitutional disclosure obligations. The majority held that a claim for Charter damages based on what we ordinarily think of as a Stinchcombe violation requires the claimant to prove that the prosecution withheld the disclosure ‘intentionally’, further defining the term with private law language about causation and harm. The reason advanced for this high standard is to protect prosecutors from a flood of litigation that would distract them from their duties or otherwise chill their discretion. Sossin takes umbrage with these flimsy justifications. In his own inimitable words:

This argument is as unsavory as it is unpersuasive. It is unsavory as it suggests prosecutors are a vulnerable group who need protection in the development of Charter damages rather than focusing on the remedy needed by those subject to state action whose Charter rights have been breached. And it is unpersuasive because the notion of a “chill” or distraction due to concerns over liability arises from a private law perspective, where officials may become more cautious where their own, personal liability may be engaged. Private law perspectives simply are unsuited to the task of identifying and enforcing public and constitutional duties. Rather than worry about whether police officers, prosecutors, national security officials or others who wield the enormous array of state law enforcement resources (and legitimacy to deprive people of their liberty) will be distracted by legal and constitutional accountability for their actions, Government could focus more usefully on recruiting, training and supporting prosecutors and law enforcement officers well versed in their legal and constitutional obligations.

Sossin expressed a preference for the minority decision penned by Justices McLachlin and Karakatsanis which emphasized public law principles and rejected the chilling effect rationale outright.

Noting the Henry decision as a low-point in 2015, Sossin remarked that “In light of Henry… it is unlikely that Charter damages will play an expanded role in the accountability of state actors.” He goes so far as to conclude that “Henry calls into question the Court’s resolve under the Charter to ensure against rights without remedies.”

Suffice to say Sossin was not a fan. Not only did the Henry majority seem to ignore every warning he advanced in his 1993 article, but it also disturbed the much-praised public law test for Charter damages in Ward.

And just when you think things can’t get worse…

2018: A Befuddling Implication: Ernst v Alberta Energy Regulator

Sossin’s skepticism of the Supreme Court’s resolve to craft principled Charter remedies was aggravated by a “puzzling” decision in Ernst v Alberta Energy Regulator.

I have read and re-read Ernst several times. Each time I read it, I understand it less. I have found that Sossin’s blog article, “Damaging the Charter”, not only summarizes this confusing case but also gives words to my gut discomfort with the decision.

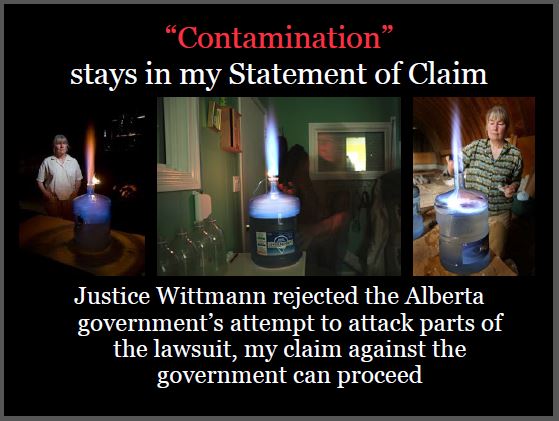

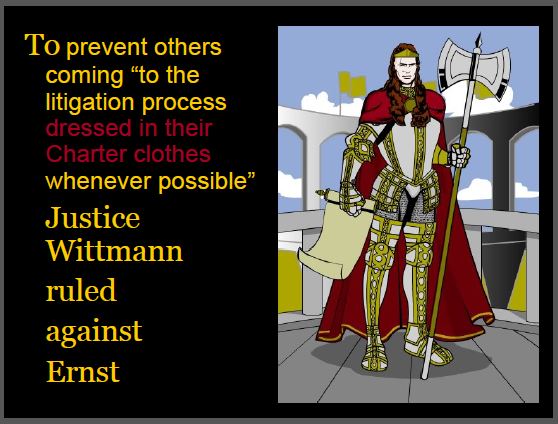

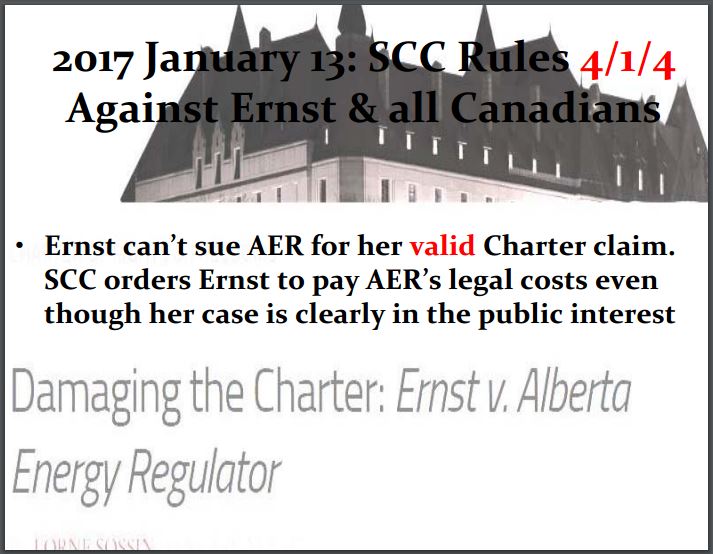

In Ernst, an individual claimant sought damages against an energy regulator. Her pleadings claimed that the regulator would not process her complaint unless and until she stopped vocalizing her opposition to the regulator’s view on fracking. This, Ernst stated, was a violation of her right to free expression in 2(b) of the Charter, and merited damages. Four judges held that a claim for Charter damages on these facts could never be appropriate against an administrative body like this regulator, and that in any event a statute barring damages against the regulator blocked her path to success (largely based on private law principles). Four judges disagreed, holding that the claim could succeed and a trial should be ordered (largely based on private law principles). One judge tipped the balance in favour of the former four, noting a fatal procedural defect in the claimant’s pleadings.

While the starting point of Sossin’s criticism is again focused on private law principles working their way into public law analyses, Sossin also comments on the more acute issue in the case: whether a statutory immunity to damages claims could ever defeat a Charter remedy. This question is not squarely addressed by the Court, though Sossin believes it was at least implied that a statute could bar a constitutional remedy.

To Sossin, this result is unstable and unprincipled. He makes the following observation about the damage caused by permitting a statute to defeat a constitutional remedy:

The availability of Charter damages, like the availability of other Charter remedies (declarations, injunctions, etc.), cannot be precluded by an act either of a provincial legislature or of Parliament (unless the notwithstanding clause under s.33 is invoked, which is the sole mechanism for immunizing public bodies from Charter scrutiny, and therefore, from Charter remedies). Legislation can also limit the availability of Charter remedies from administrative tribunals and regulators, but here, the remedy sought is from a Court.

Note that while Sossin concedes that the notwithstanding clause can bar a substantive claim, and therefore its remedy, even the notwithstanding clause by its own terms cannot preclude a remedy directly.

Thus, the Ernst decision appears to empower legislatures to circumvent Charter compliance through mere legislation without the social and political cost of invoking the constitutional bogeyman.

In a closing befitting of his concerns, Sossin concludes that “this first judgment of 2017 has damaging potential to erode the enforcement of Charter rights.” Sossin’s concerns remain essentially the same – he even refers to his 1993 piece – and places the onus on the Court to provide clearer reasons for its determination to use private law principles in Charter cases.

Concluding On a Personal Note…

At the 2018 Constitutional Cases Conference, I had a brief chat with then Dean Sossin about my own graduate work on this subject. He invited me to email him a draft of my thesis. I never did, mostly because I was too shy to share a work in progress with someone to whom writing seems to come so easily. ![]() Bummer!

Bummer!![]()

Now that he is on the bench, I will only ever email him through the judicial secretary, and certainly not my own thesis. It may go without saying that I think Justice Sossin will be an asset to the administration of justice in Toronto. My hope is that his contribution to Charter damages scholarship will rematerialize as strong Charter damages decisions. ![]() Me too! If anyone can heal the damages done to our Charter by the Supreme Court of Canada it’s Justice Sossin. Given his keen care for our Charter, I expect he found your thesis online and read it. I just found it, and will read it tomorrow. I see you included my case. I am honoured. Thank you for also caring about the Charter (and most importantly, it’s purpose that our courts seem to want to deny). I love our Charter deeply, only to be betrayed (and devastated) by the Supreme Court of Canada – 7/9 of the judges that heard my appeal were appointed by the Harper gov’t. When I saw the 2011 federal election results, I knew my case was lost before it even started because of the anti-Charter judges Harper would put on the bench. He appointed most of the judges involved in my case in Alberta also, and worse shuffled them back and forth causing me extra costs and lost time. Add to that, my lawyers (Murray Klippenstein and Cory Wanless) betraying me, lying to me, abruptly quitting on me, my case and the public interest 1.5 years after the Supreme Court betrayed me, contrary to the legal profession’s rules and still withholding my case files, with no consequence except harm to me and my case (after sacrificing nearly $400,000.00). Klippensteins did not quit other cases taken on years after taking on mine (G20 that settled – on the backs of ordinary taxpayers, protecting the status quo and which has been nominated for Class Action Team of the Year, Canadian Law Awards 2021; Choc vs Hudbay case; and Klippenstein recently chased a law-violating COVID denier). Prejudice by one’s own lawyers? Access to “justice” in Canada meanders around in Hell, going nowhere for ordinary citizens. PS In 2011, Klippenstein advised me not to fret about Harper’s judges, that sometimes old conservative judges change how they rule because they know death is approaching and want to something right before they die (this did not give me any comfort; turns out I was right to be worried – Harper appointed some doozies).

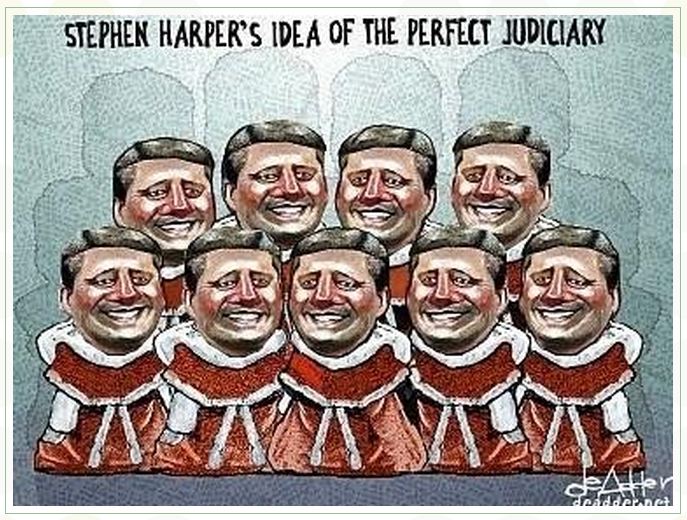

Me too! If anyone can heal the damages done to our Charter by the Supreme Court of Canada it’s Justice Sossin. Given his keen care for our Charter, I expect he found your thesis online and read it. I just found it, and will read it tomorrow. I see you included my case. I am honoured. Thank you for also caring about the Charter (and most importantly, it’s purpose that our courts seem to want to deny). I love our Charter deeply, only to be betrayed (and devastated) by the Supreme Court of Canada – 7/9 of the judges that heard my appeal were appointed by the Harper gov’t. When I saw the 2011 federal election results, I knew my case was lost before it even started because of the anti-Charter judges Harper would put on the bench. He appointed most of the judges involved in my case in Alberta also, and worse shuffled them back and forth causing me extra costs and lost time. Add to that, my lawyers (Murray Klippenstein and Cory Wanless) betraying me, lying to me, abruptly quitting on me, my case and the public interest 1.5 years after the Supreme Court betrayed me, contrary to the legal profession’s rules and still withholding my case files, with no consequence except harm to me and my case (after sacrificing nearly $400,000.00). Klippensteins did not quit other cases taken on years after taking on mine (G20 that settled – on the backs of ordinary taxpayers, protecting the status quo and which has been nominated for Class Action Team of the Year, Canadian Law Awards 2021; Choc vs Hudbay case; and Klippenstein recently chased a law-violating COVID denier). Prejudice by one’s own lawyers? Access to “justice” in Canada meanders around in Hell, going nowhere for ordinary citizens. PS In 2011, Klippenstein advised me not to fret about Harper’s judges, that sometimes old conservative judges change how they rule because they know death is approaching and want to something right before they die (this did not give me any comfort; turns out I was right to be worried – Harper appointed some doozies).![]() And like many of his students, I look forward to appearing before his Honour in the near future.

And like many of his students, I look forward to appearing before his Honour in the near future.

In Canada, we have a constitution with remarkably broad remedial capabilities; but when it comes to Charter damages, our prayers for relief have been few and far between. That is, until very recently. Since 2010, Charter damages are on the rise. This blog tracks some of the more interesting Charter damages cases and drudges up old questions on government accountability.

This blog is an outgrowth of my graduate work at Osgoode Hall Law School on Charter damages doctrine. I hope it serves as a helpful resource for anyone interested in this growing area of practise and research. …

CHARTER DAMAGES: PRIVATE LAW IN THE “UNIQUE PUBLIC LAW REMEDY” A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN LAW GRADUATE PROGRAM IN LAW OSGOODE HALL LAW SCHOOL YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO September 2018 © Peter Adourian, 2018

Refer also to:

Dead girl has charter rights, lawsuit against RCMP can go ahead: ruling

The Charter proves to be Canada’s gift to world Pfffffft!

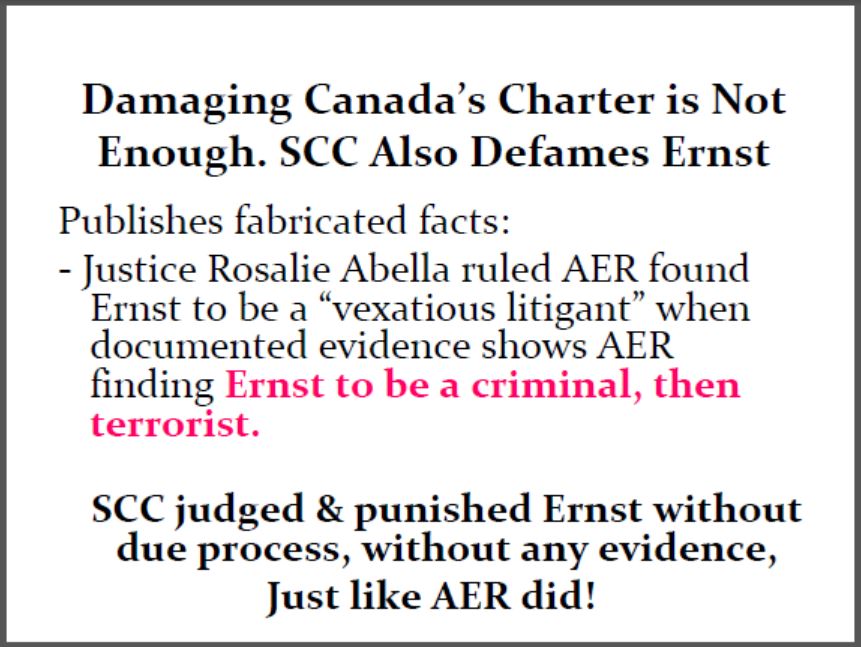

Supreme court of Canada pisses on the rule of law, damages Canada’s Charter and knowingly lies in their ruling in Ernst vs AER. Worse, the court sends the lie to the media but not the part of their ruling where the lie is pointed out.

7/9 of the judges that ruled against Ernst and the Charter were appointed by then PM Steve Harper, Charter-hater.

Slides above from Ernst Presentations

2015: Scary! Stephen Harper’s courts: How the judiciary in Canada has been remade

Email to Ernst:

… You’ve proven that oil companies are above the law. Such a hard won victory for you but what a foot hold for others pursuing claims against oil companies in the future. Dragging the dark into light is the work of giants and you did it!

I hope this finds you in good spirits.

Thank you again for staying the line

Deb Macleod

Rick Wyrozub [Alberta lawyer]

***

Emmett Macfarlane@EmmMacfarlane Poli Sci Prof, UWaterloo. Constitutional Law, Public Policy & Cdn Politics:

Law is politics people. Never forget.