Chinese-owned company Sinopec fined $150,000 over Alberta pipeline spill by The Canadian Press, November 7, 2014, The Globe and Mail

Two days later, the contractor realized that no water was flowing into a disposal well, despite the fact the well was producing.

“(He) then realized the pipeline must be leaking,” the statement says. ‘He immediately shut the pipeline down and notified his foreman.’

The spill sent 391,000 litres of contaminated, salty water into Marsh Head Creek, a tributary of the Athabasca River.

That was enough to exceed allowable levels of those contaminants 7.4 kilometres downstream of the spill.

“No dead fish were actually observed because Marsh Head Creek was covered with snow and ice at the time of the release,” says the statement.

… According to an agreed statement of facts, the spill happened as a result of a contractor’s attempts to restart compressors at two wells, which produced a mix of natural gas, hydrocarbon liquids and salty, contaminated water. [Emphasis added]

Marsh Head Creek, Division 18, Alberta

Marsh Head Creek is a stream located just 19.1 miles from Fox Creek, in Division 18, in the province of Alberta, Canada. Whether you’re spinning, fly fishing or baitcasting your chances of getting a bite here are good. So grab your favorite fly fishing rod and reel, and head out to Marsh Head Creek. For Fishing License purchase, fishing rules, and fishing regulations please visit Alberta Fish & Wildlife. Please remember to check with the local Fish and Wildlife department to ensure the stream is open to the public. Now get out there and fish! Check out our Fishing Times chart to determine when the fish will be most active. [But, don’t eat what you catch and watch your skin if it gets wet]

Fracturing Fluid Flowback Reuse Project by MI SWACO, a Schlumberger Company for Petroleum Technology Alliance of Canada and the BC Science and Community Environmental Knowledge (SCEK) Fund, 2011

Currently, there are no regulations for NORM management in Canada, however, the ERCB provides guidelines outlining NORM waste disposal options in Directive 058: Oilfield Waste Management Requirements for the Upstream Petroleum Industry.

The largest-volume oil and gas waste stream that contains NORMs is produced water. At this time, the radium content of produced water going to injection wells is not regulated.

[Emphasis added]

NC toxicologist: Water near Duke’s dumps not safe to drink by Michael Biesecker, August 3, 2016, Associated Press in Marcellus.com

WASHINGTON (AP) — North Carolina’s top public health official acted unethically and possibly illegally by telling residents living near Duke Energy coal ash pits that their well water is safe to drink when it’s contaminated with a chemical known to cause cancer, a state toxicologist said in sworn testimony.

[Where are the Canadian water experts and authorities to testify that Alberta Environment and AER acted unethically and illegally telling Alberta residents their drinking water is safe to drink when the regulators knew and still know that it’s highly explosive after being contaminated by Encana, and that none of the Canadian authorities are compelling Encana to disclose the chemicals the company illegally injected into the drinking water aquifers?]

The Associated Press obtained a copy of the 220-page deposition given last month by toxicologist Ken Rudo as part of a lawsuit filed against Duke by a coalition of environmental groups.

The nation’s largest electricity company has asked a federal judge to seal the record, claiming its public disclosure would potentially prejudice jurors.

Rudo’s boss, state public health director Dr. Randall Williams, in March reversed earlier warnings that had told hundreds of affected residents not to drink their water.

The water is contaminated with cancer-causing hexavalent chromium at levels many times higher than Rudo had determined is safe.

[Chromium Cross Check:

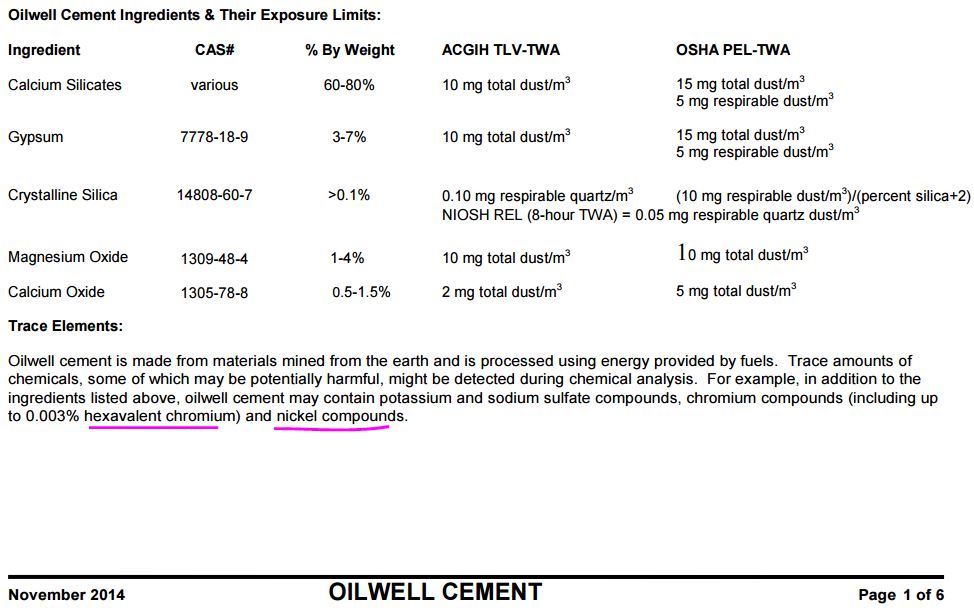

Hexavalent chromium is commonly used as gel breaker in fracs and Class “G” cement used in oil and gas wellbores:

Example of Class G Cement: API Oilwell Cement, Class ‘G’, Moderate Sulphate Resistant

CAS #: 65997-15-1. Snap taken June 11, 2015

Encana pumped masses of frac fluids and cement into Rosebud’s drinking water aquifers. Neither AER nor Alberta Environment publicly disclosed to the community, or public, that hexavalent chromium was found in Rosebud groundwater sampled by Alberta Environment.

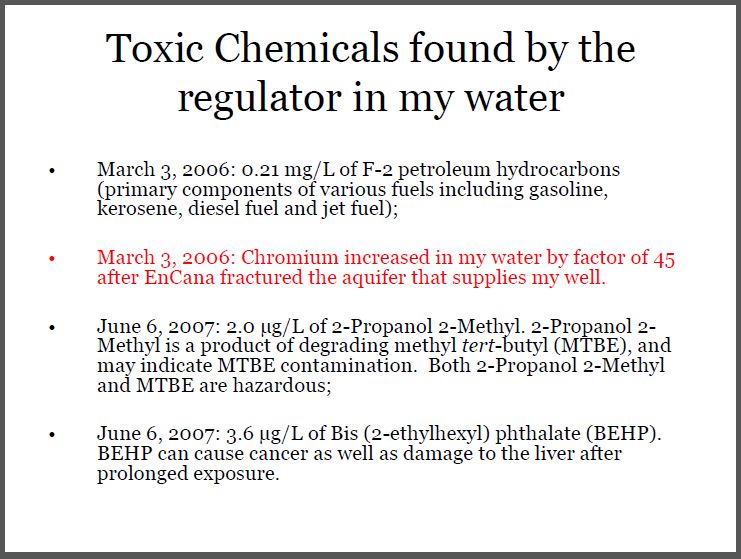

Ernst’s water was tested in 2003 for metals (including chromium) by Encana before the company’s illegally frac’d the aquifer that supplies her water well. Alberta Environment tested her water for metals (including chromium) after Encana’s illegal aquifer fracs. The chromium in her water increased by a factor of 45 after Encana’s aquifer fracs.

The regulators did not tell this to Ernst or inform her community or the public. Instead, Alberta Environment’s lead investigator Kevin Pilger introduced gopher shit into a neighbouring water well and then the regulators, Dr. Alexander Blyth with the Alberta Research Council and Encana blamed Ernst for poor maintenance on her well causing the contamination in her water.

End Chromium Cross Check]

“The state health director’s job is to protect public health,” testified Rudo, who has been the state’s toxicologist for nearly 30 years. “And in this specific instance, the opposite occurred. He knowingly told people that their water was safe when we knew it wasn’t.”

Rudo also described being summoned for a highly unusual 2015 meeting at the office of Gov. Pat McCrory, a Republican who worked for Duke Energy for nearly three decades prior to his election. McCrory was away and listened in on the phone as his communications director, Josh Ellis, asked Rudo why it was necessary to warn the residents.

“Their concern was initially telling people not to drink the water,” Rudo testified. “They felt that was a strong thing to do.”

Rudo said the water warnings were required under state law once testing had shown the wells to be contaminated at what he had determined were unsafe levels of a cancer-causing chemical.

Kendra Gerlach, communications director for the state Department of Health and Human Services, said she was also in the meeting in Ellis’ office and said McCrory did not “participate.”

Asked if she was accusing Rudo of lying under oath about McCrory being on the phone during the meeting, Gerlach responded, “Absolutely not.”

Later, McCrory’s office issued a statement quoting chief of staff Thomas Stith that accused Rudo of lying about whether McCrory took part in the meeting. Stith was not in Ellis’ office during the exchange.

Rudo told the AP late Tuesday he stood by his sworn testimony, which he said was supported by emails and his notes.

“I was speaking under oath, they are not,” said Rudo.

McCrory and his close ties to Duke Energy have been under scrutiny since a massive 2014 spill from one of the company’s coal ash dumps coated 70 miles of the Dan River in gray sludge. McCrory is running for re-election in November.

Environmentalists complain McCrory’s administration stymied efforts to hold Duke accountable for polluting groundwater. McCrory denies any preferential treatment to his former employer.

Before the spill, McCrory’s administration had proposed settling environmental violations at Duke’s power plants for a total of $99,000 in fines. Afterward, Duke was forced by federal prosecutors to plead guilty to nine violations of the Clean Water Act at five plants, agreeing to pay $102 million.

Rudo testified his office was pressured by administration officials to add misleading and confusing language to the warning letters to be sent to residents. State officials finally issued letters without Rudo’s signature to the owners of 330 water wells near Duke coal-burning plants, some of which showed hexavalent chromium levels far higher than the state’s warning level — a one-in-a-million risk for a person to develop cancer.

Concerned that the letters played down the public health risk, Rudo said he had refused to sign them, and later made hundreds of phone calls to personally tell affected residents not to drink their water.

Hexavalent chromium can cause lung cancer when inhaled, and the Environmental Protection Agency says it’s likely carcinogenic when ingested. In his deposition, Rudo said the chemical would cause an increased lifetime risk of causing tumors in those who drink it, especially pregnant women and children.

That and other toxic chemicals such as lead and arsenic are contained in coal ash, the byproduct generated after coal is burned to generate electricity. Duke denies its massive coal ash dumps are the source of the contamination, though it agreed to voluntarily provide bottled water to the affected households ringing its power plants.

Williams, an obstetrician and gynecologist who had worked in private practice, was appointed as state health director in July 2015, after the initial warning letters were issued.

Rudo testified that his new boss questioned whether the one-in-a-million risk standard laid out in state law was too strict when applied to the well water near Duke’s coal ash pits. In countermanding the earlier decision, Williams adopted Duke’s view that the standard was too cautious.

Rudo holds a doctorate in environmental toxicology, the study of the harmful effects of various chemicals on the human body. Williams signed the letters reversing the decision himself, after another public health official in Rudo’s department refused on ethical grounds, according to the deposition.

Duke Energy argued in court papers earlier this month that Rudo’s deposition should be kept private because the company’s lawyers had limited opportunities to question him during the July 11 deposition.

“We have hours’ worth of questions in response to the testimony provided by Dr. Rudo,” said Paige Sheehan, a spokeswoman for the company. “His deposition is only about half completed and lawyers are just beginning to challenge Dr. Rudo’s motives, his claims and his credibility.”

___

Associated Press writer Emery P. Dalesio contributed to this report from Raleigh, N.C. [Emphasis added]

In Texas, wastewater spills get less scrutiny by Mike Soraghan, E&E News, August 2, 2016

In Texas, there were more than 2,700 spills at oil and gas sites last year. But the state tracked only about half of those.

Unlike other states, Texas doesn’t track spills of wastewater. The Texas Railroad Commission (RRC), which regulates oil and gas, tracks only spills of petroleum products — primarily crude oil.

The difference in scrutiny makes no sense to Kerry Sublette, a chemical engineering professor at the University of Tulsa who says wastewater spills are more damaging.

“If you were trying to prevent spills,” Sublette said, “wouldn’t you want to look at what’s causing them? Where they’re happening? All that kind of information?” [Where in the world do energy regulators or companies give a damn about preventing spills, of any kind?]

Records compiled by EnergyWire show there were at least 2,732 spills reported to RRC district offices in 2015. The agency’s record of spills of crude oil and condensate includes 1,485 spills, about 54 percent of the total number.

Those were among at least 10,348 spills and other mishaps across the country in 2015, compared with 11,283 in 2014, according to an EnergyWire analysis. In the 17 states where comparisons could be drawn, the number of spills dropped 8 percent (EnergyWire, July 21).

The RRC, whose name is a holdover from an era in which oil was transported by trains instead of pipelines, is one of the few agencies to post enforcement data. The agency reported finding 18 violations of spill reporting rules in 2015, and no violations of its oil spill regulations.

All spills are supposed to be reported to RRC district offices, though there is documented confusion about that requirement. In most offices, the mishaps get logged on spreadsheets.

If the spill is crude or condensate, and it’s five barrels or more, the company must follow up with a specific form. Called an “H-8,” the form requires information about the extent of the spill and how it’s being cleaned up.

The H-8 forms are compiled, and data about them are posted on the RRC website.

But no such scrutiny is applied to spills composed entirely of wastewater, often called brine, salt water or produced water.

So, Cimarex Energy Co. didn’t have to file a spill form after a crew lost control of the company’s Sawtooth 55-6 well and spilled more than 700,000 gallons of wastewater in February 2015. The spill in Reeves County, west of Odessa, occurred after a gasket leaked, according to the district office spill log.

RRC officials say the spills must be cleaned up, but critics question how the agency can ensure proper cleanup if incidents aren’t tracked.

In response to questions about spill reporting and tracking, RRC spokeswoman Ramona Nye stressed that agency rules prohibit polluting water with any oil field fluid, including wastewater. The agency reported 261 violations of its water protection rules in 2015. [Are the RRC rules working?]

“Protection of public safety and our natural resources is the Railroad Commission’s highest priority,” Nye said.

To get the spill totals for Texas, EnergyWire filed an open records request for the spill records from the agency’s 11 district offices. The district office in Wichita Falls, covering the Panhandle, doesn’t keep a spreadsheet of spills.

Large onshore oil spills can be dangerous to humans in the communities where they occur. But experts say brine spills are as damaging as oil spills to soil and plants — sometimes much more so.

Oil can be scraped away, and what remains degrades over time. Salty, toxic wastewater can penetrate deeper into soil, reaching groundwater more easily and turning productive farmland into concrete-like hardpan.

“Unlike oil, time is not a cure,” said Duke University geochemist Avner Vengosh, who has studied wastewater spills in several states (Greenwire, April 28). Researching spills in North Dakota, he and colleagues would visit sites of years-old spills and “find the brine there waiting for us to collect it.”

Large spills can take companies years to clean up. And Sublette said if a spill isn’t cleaned up, nothing will grow on the affected area for generations.

“It’s the gift that keeps on giving,” he said.

Sublette believes spill numbers documented in the district office logs are an undercount. He teaches workshops on spill cleanup, and in Texas he routinely meets oil company people who don’t think that wastewater spills need to be reported to the state.

RRC representatives stress that operators are required to report any spill. But that’s not always the understanding of those outside the agency’s media affairs office. Last year, the agency’s former director told EnergyWire that while cleanup is mandatory, reporting is voluntary [meaning that clean is voluntary too?] (EnergyWire, Nov. 18, 2015).

And a manager for the University of Texas’ University Lands system said his agency uses a spill cleanup guide that incorporates a 2005 RRC draft guide that says “all produced water notifications are voluntary.”

“A lot of producers, they do not feel that they are compelled to report brine spills. That’s their perception,” Sublette said. Some companies, especially larger ones, report anyway because it’s corporate policy. But, he said, “It appears some smaller companies are confused [Intentionally?], or are taking advantage of the confusion.”

Click here to see the EnergyWire national database of spills.

Click here for information about the data. [Emphasis added]

TENORM in KY Landfills: Loopholes, Questionable Business Practices by Dan Heyman, August 3. 2016, Public News Service

CHARLESTON, W.Va. – Behind the low-level radioactive waste dumped in a Kentucky landfill are regulatory loopholes and questionable business practices [Where did the “best” go?], according to state and local documents.

Tom FitzGerald, director of the Kentucky Resources Council, obtained correspondence between Kentucky and West Virginia officials, and said it showed that regulators didn’t coordinate. In the confusion, he said, several firms run by the same person dumped “Technologically-Enhanced, Naturally-Occurring Radioactive Materials” from West Virginia and Ohio fracking operations into the Estill County landfill. One company, Advanced TENORM Services, came to light first.

“The landfill records in Estill County, which showed a couple of other companies had shipped TENORM waste,” he said, “one being Nuverra, I believe, and another being a Cambrian Services.”

According to state filings, Cory Hoskins operates Advanced TENORM Services out of the West Liberty, Ky., public library. Landfill records show him as the head of Cambrian Well Services and Nuverra, both based in Norwich, Ohio. Hoskins has not returned numerous calls and messages.

Mike Manypenny, a former Taylor County delegate and current congressional candidate, said dust from TENORM can lodge in the lungs and cause cancer. He worked in the Legislature to keep hot frack waste from creating problems in West Virginia landfills. West Virginia isn’t coordinating the frack-waste disposal with the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission, let alone other states, he said.

“We need to have a cradle-to-grave monitoring system to make sure that we know where these materials have come from, and where it ends up when it’s disposed of,” he said.

The view from Kentucky is similar, said FitzGerald.

“Everyone seems to be mostly concerned about what’s going on in their own state,” he said, “rather than assuring that wherever these wastes are going, that they’re going to a place that is properly operated and managed.”

State officials in Kentucky have decided to pursue civil but not criminal charges. They say the waste is safer where it is, rather than being dug up again.

More information on TENORM is online at epa.gov. [Emphasis added]

[And then there’s Encana, dumping its waste on foodland at Rosebud: