Peace River hearings test new oilpatch enforcer by Sheila Pratt, January 31, 2014, Edmonton Journal

In a slightly drafty conference room just off main street, far from oil company office towers, hearing commissioner Brad McManus and three panellists face the first big test of Alberta’s new oilpatch enforcer. For eight days in late January, the panel from the Alberta Energy Regulator listened intently as area farmers expressed concerns that air pollution from 86 bitumen tanks around their farms south of Peace River were making them ill. Five families have moved away from the Reno area, two during the two weeks of the inquiry.

Calgary-based Baytex Energy, which has operated the Reno tanks since 2011, pointed out that studies show air pollution in the area is well below Alberta’s thresholds for toxic levels. Baytex soon told the panel the company intended to install vapour recovery units on all tank tops to capture the emissions coming off the heated bitumen, which would meet the key request residents had been making for two years. That had been the company’s intent all along, but it was poorly communicated, Marty Proctor, Baytex chief operating officer, later added in comments to the inquiry.

Residents from Three Creeks, north of Peace River, also brought long-standing concerns about emissions from the field where five companies operate, Shell, Husky Murphy, Baytex and Penn West.

In many ways, McManus, chief hearing officer, and the panel — and the public — were watching the classic Alberta conflict between landowners and oil companies.

It’s happening now in Peace River partly because oilsands operators are drilling aggressively in a populated farming area rather than the middle of wilderness near Fort McMurray.

The big boom is just around the corner, with Shell ready to build a 1,500-person work camp this spring just outside town for workers building its $3 billion thermal (underground) in situ project at Carmon Creek to the north. The project will produce 80,000 barrels of oil a day by pumping steam underground to melt the bitumen.

But the special issues being dealt with at this inquiry involve a different production process, called CHOPS — Cold Heavy Oil Production with Sand — that is planting hundreds of tall, black tanks across the landscape, on farms and in the bush. CHOPS is the only production method that heats bitumen on the surface, rather than underground, to separate oil and sand. That means fumes from heating heavy oil (that stay underground in most other operations) can be released into the atmosphere unless the tanks have vapour recovery systems. Evidence at the inquiry showed there are no regulations covering hydrocarbon emissions from these tanks; no requirement to capture the vapours that can spread off site into people’s homes. There is little research into exactly which chemicals being emitted might be, although known chemicals include potential carcinogens benzene and toluene. The inquiry also heard that oilsands deposits near Peace River have much higher sulphur content than deposits in northeast Alberta. As a result, emissions from heating this bitumen Peace River will be more problematic.

Area residents, the public and oil companies will be watching the Alberta Energy Regulator very closely to see how seriously it takes their concerns. The results will be the first signal of how this new, reorganized agency will deal with the competing interests of oil companies, worried citizens and communities under pressure.

Also, later this year, as part of the Alberta government’s new deal for the industry, the regulator takes over responsibility for enforcing all environmental laws in the oilpatch, including the Environmental Protection and Enhancement act, the water act and public lands act. The Peace River report may yield some clues on how the regulator will operate on this front too.

-To find the black, three-storey tall tanks, you can drive south from the Peace River to the now abandoned Labrecque farm, or drive north of town to county road 842. The tanks sit above the wells which auger up the thick, sticky mixture from 600 metres below. The oilsand mix, the texture of thick peanut butter, is pushed up into the tanks where it is heated to separate the oil, sand and water. As the bitumen rises to the top of the tank, it flows over into the second tank and the water and sand fall to the bottom of the first. All day and all night, steel tanker trucks pull up to the tanks, fill up with the hot tarry bitumen and head off to processing plants. Each tank can hold about 1,000 barrels of oil.

Alain Labrecque, who recently moved out of his farm because of the emissions, said there’s an easy way to understand this smell: “Put a can of oil on the table and turn the heat on under it.”

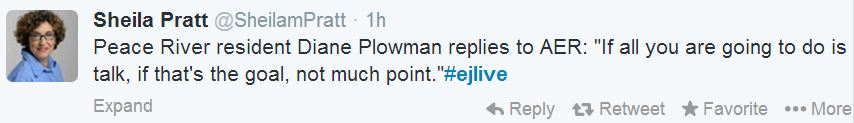

-On day five of the inquiry, three residents from Three Creeks told the inquiry of a “gassing” the day before. Strong smelling fumes floated through their homes at 2:30 in the morning, leaving them with headaches and dizziness. Carman Langer immediately called to alert the AER and left his house. Diane Plowman waited until 7:30 a.m. to phone. The local AER office ordered the companies to check out the complaints. All five companies reported 12 hours later that they found no problems. Operators there include Penn West, Shell, Baytex, Murphy Oil and Husky. So residents want independent inspectors “so companies aren’t checking up on themselves,” Plowman told the inquiry.

On day seven in the conference room, the panel called on all parties to suggest some solutions.

Calgary engineer Stephen Ramsay, hired by the AER to provide independent advice, told the panel the best way to eliminate pollution problems is to capture all bitumen vapours coming off the tanks. That means installing vapour recovery units — estimated at $120,000 to $ 200,000 for a unit that could serve several tanks, the inquiry heard. “If we want to be certain we are eliminating the odour source, we have to use a sealed system,” Ramsay said. He recommended putting all emissions, both the excess natural gas that comes up with the bitumen, and the vapours, to good use — burning them to help heat the bitumen on-site.

The question of whether to flare (burn off) the bitumen emissions drew mixed reviews.

The panel will also look at a request by Reno residents to shut down Baytex operations until that tank-top equipment is installed.

Shell Canada, which operates dozens of CHOPS tanks in the nearby Three Creeks area, told the inquiry its company policy is to capture all emissions, tank top vapours and “casing gas” that comes up with the bitumen and ship it all off to burn for power. The AER should make it a condition of approval that any new project must capture all excess natural gas and bitumen emission (called “conservation gas”), Malcolm Mayes, Shell general manager, told the inquiry. Shell would also support requiring all operators to put in gas conservation equipment on existing operations, Mayes said.

Calgary odour expert David Chadder, an expert in air quality at consultants RWDI Air, said the regulator needs “clear criteria to enforce compliance” to reduce odours. Rather than relying on company workers to check odour complaints, he suggested training people to do foot patrols and identify odours, said Chadders, a vice-president of RWDI who has worked on other industrial facilities. These so called “ odour rangers” are already being trained for the Fort McMurray area, he noted.

Resident Doug Dallyn also told the inquiry a lot of emissions are put into the air when the tankers trucks are refilled. The air inside the tanks is contaminated from the heated bitumen and it is pushed out into the atmosphere when the tank is refilled. It happens dozens of times a day.

The inquiry opened up the contentious issues of health impacts of the oil industry. Residents described dizziness, cognitive impairment, passing out, headache, fatigue, and other complaints. Like most in the Peace River area, Mike Labrecque was supportive of the oil industry when it came to his farm. He told the inquiry he worked for years in the oilpatch, including for Baytex — until he got too sick and he realized the source of his health problem. “We aren’t against the industry. We just want the problem fixed,” he said.

Vivian Lalaberte told the panel she spent her 60th birthday last week packing up a few things before abandoning the farm in the Reno field that had been in her husband Marcel’s family since the 1920s. They first left their farm in October 2012 for seven months, feeling ill. They came back in June 2013 hoping Baytex would have fixed the tank tops and contained the emissions. But the family’s symptoms soon came back.

“This isn’t a game; we are sick. This field has to be shut down or the field evacuated until the problem is fixed,” Lalaberte told the inquiry.

“If there are companies that can do a better job and put in vapour recovery, what are we waiting for?”

“We worked all our life to pay for the farm but I don’t like the way we are being treated now,” she said.

“And I don’t like it when I hear (Premier Alison) Redford say we are environmental leaders.”

…

The panel will make its recommendations public on the AER website in March. It’s unclear who has the final say on its recommendations — the minister of energy (now Diana McQueen) or the chairman of the Alberta Energy Regulator board of governors, former oilpatch insider Gerry Protti. [Emphasis added]

Screen grab, Edmonton Journal, January 31, 2014:

Article by Darcy Henton February 3, 2014, Calgary Herald:

[The] sunshine list does put a spotlight on the high rollers in government, such as deputy health minister Janet Davidson, who negotiated a salary of $577,777 that jumps to nearly $644,000 when cash benefits and allowances for professional and personal development are included. “She is the highest paid deputy minister by far, and it just goes to show a corporate culture that is kind of creeping into the public service,”

Emissions hearing told vapour recovery system only sure way to eliminate odours by Sheila Pratt, January 29, 2014, Edmonton Journal

Calgary engineer Stephen Ramsay recommended at a public inquiry Thursday that companies using heated bitumen tanks be required to install vapour recovery systems to reduce emissions into the air. “If we want to be certain we are eliminating odour source, we have to use a sealed system,” Ramsay said. … Ramsay, hired by the regulator to provide independent advice, also told the inquiry that Alberta only has regulations related to three of the 160 chemical compounds found in emissions discussed at the inquiry. [Emphasis added]

Oil field fumes so painful, Alberta families forced to move, Severe headaches, dizziness, rashes and loss of memory: all symptoms reported to a new hearing examining health effects of Alberta’s rapidly expanding heavy oil industry by Mychaylo Prystupa, January 26, 2014, Vancouver Observer

Northwest Alberta grain farmer Alain Labrecque recalls the first winter in 2011 when the fumes from oil tanks near his home in the Peace River area seemed to trigger terrible health effects for himself, his wife and two small children.

“I started getting massive headaches. My eyes twitched. I got dizzy spells. I often felt like I was going to pass out.”

“Next thing I knew, my [3-year-old] girl had trouble walking. She had no balance. She would sit at the table, and she would just fall off her chair.”

“My [4-year-old] son – he was really black under his eyes all the time, and had big time constipation.”

“Then my wife fell down the stairs while carrying a laundry basket.”

“We went through a weird winter like that,” Labrecque told the Vancouver Observer by phone Sunday.

Labrecque, his family, and neighbours are part of a group of rural home owners now giving testimony to an unprecedented Alberta hearing, examining the health effects of the odour and emissions from bitumen extraction. About 75 people packed the conference centre, each day of the first week of proceedings.

At least six families have abandoned their homes, citing health concerns from heavy oil emissions from the Reno field, about 500 km northwest of Edmonton. The hearing is also examining odour and emission concerns for the rapidly growing heavy oil industry in the wider Peace River area, which includes operators Shell Oil, Penn West, Murphy Oil, and Husky Oil.

The Reno operation consists of 86 bitumen oil storage tanks, run by Calgary-based Baytex Energy. On Friday, Alain, his wife Karla, and Alain’s uncle gave emotional testimony to the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) forum on how this field has torn their lives apart. The AER is an industry-funded oversight agency. A pad of four heavy oil tanks is just 500 metres from Labrecque’s home. Another 16 tanks are another 1,000 metres further. The tanks release a toxic, flammable and aromatic vapour that includes volatile organic compounds, benzene, toulene and sulfur, an engineer testified. The hearing revealed that Baytex did not initially install vapour recovery systems. “In 2010, the facility and tank design in use at 4 Baytex sites did not capture emissions from tank tops,” Baytex’s Alberta and BC business unit VP Rick Ramsay admitted in his testimony.

Kids waking up soaked in chemicals

Labrecque says his small children Alec and Candace would often wake up soaked, trying to “sweat the chemicals” out, resulting in rashes and burns. Fed up and terrified, he eventually moved his family to Smithers, B.C., even though he was enjoying his best income ever as a farmer in Alberta. “I grossed a million dollars. But I just couldn’t stay there,” said Labrecque. He prays his children have not suffered long term, but says many in his family continue to suffer memory loss, reduced sense of smell, and extreme chemical sensitivities.

“We’ve all become so sensitive now. My uncle can’t even fuel his truck. Any emissions give him a headache right away.”

“[My wife] can’t go into a pool with chlorine. If she does, it will trigger a huge headache, and won’t be able to function for a day. Windshield fluid is the same thing. She can’t use it.”

“Then recently, we tried snowmobiling. She tried it for five minutes, and she was bed-ridden until the next day,” said Labrecque.

Expert toxicology testimony given at the hearing suggested sulphur from the tanks may be the main health concern. An industry expert disputed this, suggesting the problem has to do with the terrible odour alone, and the effects are not as bad as reported by families.

A Baytex-commissioned air study showed that concentrations of the chemicals of concern found down wind from the tanks were below guidelines. Following complaints, Baytex executives said they took proactive measures to control the emissions, and the company is “committed to operating in a safe, environmentally responsible manner.” The Alberta hearing continues this week until Friday. [Emphasis added]

Residents who lived near Baytex oil operations tell hearing why they moved away by Sheila Pratt, January 24, 2014, Edmonton Journal

Mike Labrecque loved his job working around well sites not far from home for oil companies including Baytex. But the day he said he felt too sick to take his equipment to a well site, he was let go by Baytex. That was April 2012 and shortly after he left his farm that is in the middle of the Reno oilsands field, Labrecque, 60, told the first public inquiry held by the Alberta Energy Regulator into health concerns from emissions from oilsands operations here. In testimony at the inquiry, three farm families, some crying, told how their health problems grew so bad they finally left their homes in the Reno field 43 km south of Peace River.

For many months, Mike Labrecque did not connect his headaches, dizziness and weight loss with fumes from the oilsands operations. That April 2012 day he drove to the Baytex field office on his land and said felt too ill to take his tractor to a well pad to pull out a truck. “I told them I can’t do it, I was afraid of losing consciousness” and if that happened while he was driving, the tractor might run into the bitumen storage tanks. In the field office “I said: Is there anything you can do? And the field officer said, ‘I will call the supervisor.’

“A short time later he said ‘Hand in your time sheets, you’re done.’ That’s how it ended.”

Labrecque thought for a long time he had a flu he could never shake. He lost 40 lbs. He noticed his symptoms began to clear up when he moved away. Karla and Alain Labrecque were the first to leave. Karla, who was home with the kids in the fumes all day had constant headaches, fell down the stairs, and watched her two-year-old daughter lose her balance too often. She contacted Baytex and at first the couple was optimistic the company would capture the tank vapours from the heated bitumen they felt were making them ill. But it was taking too long and “we ran out of time.” They took the hard decision to leave their land and move to Smithers, B.C. where they continue to farm. “We knew we had no future there,” Karla said. “And today it is not fixed,” added her husband. The Labrecques are part of an extended family.

Baytex had plans for a gas conservation pipeline and at the hearing confirmed a commitment to install a vapour recovery system. Brian Labrecque told the inquiry the first time residents saw that commitment was in Baytex documents filed for the hearing. “That was not offered to us.”

The AER called the public hearing after then energy minister Ken Hughes visited the area and called on the regulator to look into the issues. In this area, Baytex and other companies use a system of augering oil and sand out of the ground and heating it in storage tanks to recover the oil. Shell testified earlier that it has vapour recover units on all its tank tops.

Some of the witnesses told the inquiry they had problems getting medical care. Karla Labrecque said one doctor she saw in the area told her to move after she said she thought her symptoms were caused by emissions from bitumen tanks near the farm. The doctor also told her about Dr. John Connor whose licence was threatened after he raised concerns about cancer rates among First Nations north of Fort McMurray. In a visit to a second doctor, Karla said she was taken aback when the doctor refused to do a blood test until he had called the local MLA. She did not ask the name of the MLA.

“He said ‘I just got off the phone with the MLA and he says it’s OK to take a blood test and fill out a form.’

“It’s not very good when you go to the doctor to get help and he has to call an MLA.” [Emphasis added]

Editorial: Sniffing out the truth by Calgary Herald, January 22, 2014

Whatever the results of a 10-day hearing that started Tuesday in Peace River to investigate whether bitumen-processing emissions are making people ill, one thing must result from this. Doctors must stop being afraid to talk about their concerns surrounding the health effects of oilsands activity. It is deeply disturbing to learn that some Peace River district doctors allegedly live with such fear, to the point that they have refused to care for residents who question whether their medical problems are connected to emissions.

A laboratory even refused to handle a test, according to Dr. Margaret Sears, an Ottawa expert in toxicology and health, who is attending the hearing. The emissions complaints centre around the Baytex Energy Ltd. operations. Nearby residents are complaining about fumes from wells and bitumen storage tanks they think may be responsible for their bouts of dizziness, sleeping problems and cognitive troubles. The Alberta Energy Regulator is holding the investigation. The doctors are afraid of repercussions, Sears says, because Dr. John O’Connor was vilified in 2006 and threatened with loss of his licence when he spoke out about the high rates of cancer in Fort Chipewyan. This kind of fear among medical professionals is intolerable. [Emphasis added]